This is an essay I published in ArtNews in 1973, a few years after I began writing for the magazine

Agnes Martin has been a painter since the early 1930s, when she came to the United States from her native Saskatchewan, Canada. However, her work didn’t mature—or, in her words, “get on the right track”—until 1957. Settling on Coenties Slip, New York, in the vicinity of Ellsworth Kelly and Ad Reinhardt, she shared with them a rejection of 1950s painterliness. During the next ten years she produced a large and consistent body of drawings and paintings in a severely reductionist mode. She makes grids, inscribing them on bare canvas or, in her drawings, superimposing them on uninflected fields of color.

In 1967, she abruptly left New York for a tract of land near Cuba, New Mexico. In the past six years she has produced nothing but an edition of prints for Parasol Press. Most of her time she has spent building houses and sheds. At present, she is at work on a studio, presumably in anticipation of a return to painting. Though six years is a long time to be absent from the New York art scene, with its rapid turnover of styles, Martin has continued to be a presiding figure here—perhaps more so now than when she was present. It is tempting to see her influence whenever one sees a grid, especially if it is penciled.

Martin is an important presence not only because she produces stylistically advanced work but also because her work is shaped by a conflict that appears at the origin of modernist art and, indeed, the modern personality. This is the conflict between the Romantic individuality and the social orientation of classicism, which has persisted through the 20th century—see (among other examples) Purism, Piet Mondrian and other artists of de Stijl, and Victor Vasarely and his Visual Research Group.

At first glance it seems that Agnes Martin is a classicist pure and simple. After all, she arrived at the austere, elegant, “impersonal” style of her maturity just as American art was finding ways beyond the Romantic excesses of Abstract-Expressionism. Furthermore, in a note from the late ’50s she says, “I would like my work to be recognized as being in the classic tradition (Coptic, Egyptian, Greek, Chinese)” (This and other quotations from Martin’s writings are from unpublished manuscripts at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.)

But it is not this simple. Granting that the Abstract Expressionists were Romantics, often self-proclaimed, were any of the reactions against them genuinely classic in spirit? Martin’s severe, low-key work seems to present one of the least qualified examples. But even here there are difficulties. The canons of beauty codified in the High Renaissance, which dominate the following centuries, put an emphasis on composition: the harmonious balance of disparate parts. Harmony of this kind has persisted through extreme stylistic variation, from the High Renaissance through Mannerism to the Baroque, from the Rococo to 18th-century Neo-Classicism, and down to the “Romantic Baroque” of Delacroix. These compositional values persisted through various romantic-classical shifts, even in phrases of completely abstract art; we see this as severe styles of geometrical abstraction develop from the baroque, “romantically” efflorescent harmonies of Synthetic Cubism.

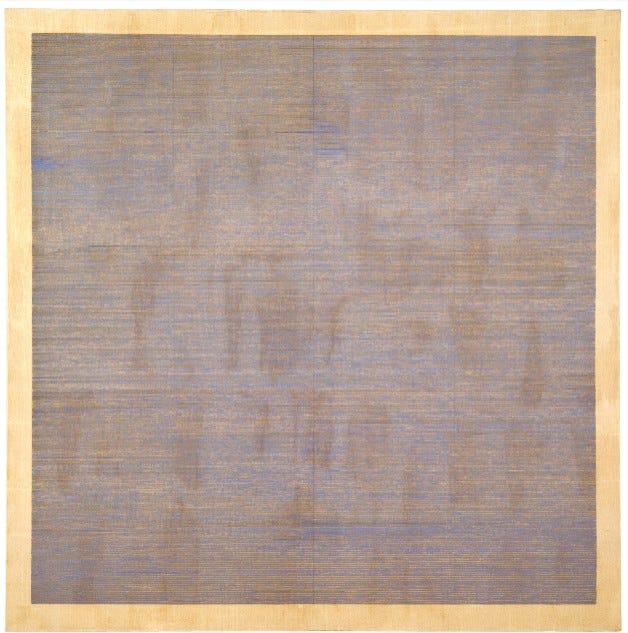

Agnes Martin’s work is outside the give and take of this history, which even at its most extravagant turns toward Romanticism maintains the ideal of compositional coherence. Balanced, composed disparity is precisely what she excludes from her mature work. Her grids are often nearly square, and they always present regular pattern—repetition, not inflected variation. Instead, her images inhabit the space of “non-compositional” Romanticism, the space of the sublime. Here—to use the terminology of Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757—a work has its effect through “a perfect simplicity, an absolute uniformity in disposition, shape and coloring,” “a successive disposition of uniform parts” which allows “a comparatively small quantity of matter [to] produce a grander effect, than a much larger quantity disposed in another manner”—the other manner being that of the classically ordered composition, which produces beauty, not the sublime, by means—in Burke’s words—of “gradual variation” in works whose parts “vary in their direction every moment, chang[ing] under the eye by a deviation of continually carrying on,” producing disparate forms ultimately unified or “melted as it were into each other.”

Representational painting, with its responsibility to the world’s visible details, achieves sublime effects only when it addresses the sea (J. M. W. Turner), the sky (John Constable), foliage (Frederick Edwin Church) or, simply, light. A “pure” sublime is available only to those artists employing arbitrary forms that can be conveniently repeated or materials that can be presented in uninflected or repetitively patterned fields: architects, composers, and abstract painters. Agnes Martin’s mature work is one of the chief modernist evocations of the “artificial infinite” of the sublime (Burke). Hence not only is she not a classicist, she is not a Romantic of the kind that develops variations on classical composition.

There are of course resemblances between the two kinds of Romanticism—the sublime and the anti-classical. Both yearn in a quasi-religious way for supra-human absolutes, which are approachable only by individuals isolated in their special capacities for artistic creation. Martin describes this traditionally Romantic, absolutist goal as “the perfect state.” She reveals her attitude toward perfection—that is, her style of Romanticism—when she says, “The establishment of the perfect state is not mine to do. Being outside that struggle, I turn to perfection as I see it in my mind, and as I also see it with my eyes, even in the dust. Although I do not represent it very well in my work, all seeing the work being already familiar with [perfection] are easily reminded of it.”

This startlingly modest way of describing herself and her sense of the possibilities for her art is in full contrast to classically based attempts to achieve a harmonious balance between the subjective and objective, the artist and the world. Romanticism tends to exalt one over the other. Agnes Martin is a Romantic of the kind who feels that the artist must leave the subjective—the ego—behind if there is to be any contact, however slight, with a true reality. She says, “It is not possible to overthrow pride. It is not possible because we ourselves are pride . . . But we can witness the defeat of pride because pride cannot hold out. Pride isn’t real as sooner or later it must go down. When pride in some form is lost, we feel very different . . . We feel a moment of perfection that is indescribable, a sudden joy in living” (From notes of the lecture Martin gave at Cooper Union, in New York, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, February 1973).

She goes on in the same lecture to say, “a sense of disappointment and defeat is the essential state of mind for creative work.” It is hard to reconcile this with her attempt to present a joyous perfection in her art, until one sees that the “disappointment and defeat” suffered by pride, by the ego, is a preparatory state. Having passed through this state by defeating pride, especially pride in artistic virtuosity, the artist can begin to represent perfection. This is summed up in a note on Buddhist doctrine, which also acknowledges the anti-classical direction of her art. She observes that there are, in reaching “true Dharma,” three levels of being. In ascending order of value, they are “the ritualistic,” “the underlying purity” which she labels “the classic” and, highest of all, “the void, pure mind, freedom.” For Martin, a Western artist in the modernist tradition, this third level can only be interpreted as a Romantic absolute—an infinite realm of perfection beyond the ego.

Her writings have a formal reflection in her grid patterns. Never fitting these patterns to her square formats, she frees them from a strict reference to their physical location on the canvas. This, along with their repetitious evenness, makes them potentially capable of unbounded expansion. They become symbols of freedom, hence symbolic evocations of a perfection beyond the individual, the inflected, the virtuosic. In addition, the style of her penciling is a symbol of the defeat of the ego. It is inexact in its linearity, hence not prideful—but it is not assertive in its inexactness either, hence it is doubly free of pride. In noticing the minute imperfections of Martin’s draftsmanship, one enters a realm leading to the infinitely small. The smallest perceivable detail of pencil line, crayoned color, paint surface, or the weave of the canvas takes on an intensity for the eye comparable to that of virtuoso stylistics. Through her fastidiousness, her reluctance to put much into her images, Martin gives an intense focus the little that is there. The intervals of her grids, especially, gain from this, achieving a clarity which rescues them from arbitrariness.

Not only in the formal qualities of her works but in their subdued, even secretive references to nature can be found her extreme version of the Romantic sensibility. Each of her grids seems to abstract an aspect of nature, not a specific shape but the generalized presence of some vast phenomenon; see Mountain, Dark River, Park, and Starlight. Alongside her titled works are others which are untitled but formally similar; these evoke phenomena so vast or elusive as to be unnamable and seem to shift from external to internal states.

From 1964 on, Martin’s works referring to the enveloping aspects of nature are joined by others referring to the individual’s responses to nature. The shift of emphasis inspires a new kind of title: Play, Adventure, Journey, Song. Form changes very little, suggesting—as her writings would lead one to expect—that Martin is interested in only the most general, stable, unspecific aspects of subjective experience. These recent titles do, however, require a shift away from “representational” color: the green pencil lines of Park and the red ones of Rose give way to the less easily interpreted near-monotones of Play and Adventure. In 1963 Martin joined elusive color to a richly ambiguous title: Falling Blue may represent a natural phenomenon, your mood when you are immersed in it, or both at once.

Thank you for articulating romantic vs classical in connection with Martin's work. Am glad too to learn of the Burke term "artificial infinite". Thanks as well for challenging Martin's description at the time of writing of her own work as fully classical. That description is as pure as Jo Baer eventually refuting minimalism for a return to figuration. There were threads with that too between her before and after. Thomas McEvilley, in a late 80s piece, pointed to a floating bouyancy as present in both. I absolutely experience tactile strands of earth and water in the image of Martin's "Falling Blue".

It is remarkable that your insights and style has been so consistent over this whole time.

The ascending issues of “the ritualistic,” “the underlying purity” which she labels “the classic” and, highest of all, “the void, pure mind, freedom” point to differences between Western Abrahamic Absolutes and Eastern Meditative Absolutes. Agnes Martin's work seems to fall into the latter while a comparable former type would be Barnett Newman's work. Mr Newman seems to have moved quickly through the Ritualistic and Underlying Purity to the pure Mind/Freedom of Abrahamic Mysticism or Western Romanticism. There is a pole or current to an absolute outer source in our Western Romanticism that sits within Enlightenment Thought, Ethics, and Values as well as the artistic inspiration of Romantic Artists, Romantic Modernists, especially the AE New York Painters.

Agnes Martin has adopted at least parts of Eastern Philosophy and Religious Practice to inform her works. This may explain why the works have a quietude and droll obedience to ritual and purity. They obviate the "self" in ways akin to Donald Judd sculpture.

After decades of exposure, this eastern quelling of excitation does distinguish Martin's painting, as it does the sculpture of the Minimalists, Judd and others.

There is a special appreciation required for this approach, perhaps a training in the arts, practices and psyche of the Eastern Culture and Religion.

I will take our Western Romantics, thank you! Pollack, Newman, Still, Delacroix, Church, Frederich, the sublime light works of the Impressionists, any and all out of the Abrahamic, Greek and Roman Mystical Traditions.

Thanks for reissuing such a poignant essay.