Many things can be cruel—parental discipline, foreign policy, gossip. Sometimes we say the weather is cruel, but this is a metaphorical way of speaking. However much it hurts us, the weather does not intend to be cruel and nothing counts as cruelty that is not intended. This stipulation makes gossip a borderline case, for we might want to allow that some of it is so idle that it can’t possibly hurt anyone—or if it does, it does so unintentionally. And what about foreign policy that causes harm by mistake, out of stupidity, not maliciousness?

Far from gray zones filled with borderline cases are things like sunsets. Aside from the difficult memories it might stir up, a sunset cannot be cruel because it is a natural phenomenon and therefore has no motive to be cruel or anything else. Unlike sunsets, works of art are intended but never, I believe, intended to be cruel. Still, some have been dismissed as hoaxes: devices designed to make people feel foolish. In the July 11, 1948, issue of The New York Times Magazine, Aline Louchheim published “The ABC (or XYZ) of Abstract Art,” an article inspired, I suspect, by the attention suddenly focused on Jackson Pollock. Next to a reproduction of a dripped and poured canvas, she wrote:

This license with traditional formulas upsets many people. They complain that much modern painting has a haphazard look, lawless and chaotic. They accuse it of slovenliness … The antagonists have another argument. This is all tommyrot, they say, charlatanism. The artist is making fun of the public and we won’t be taken in.

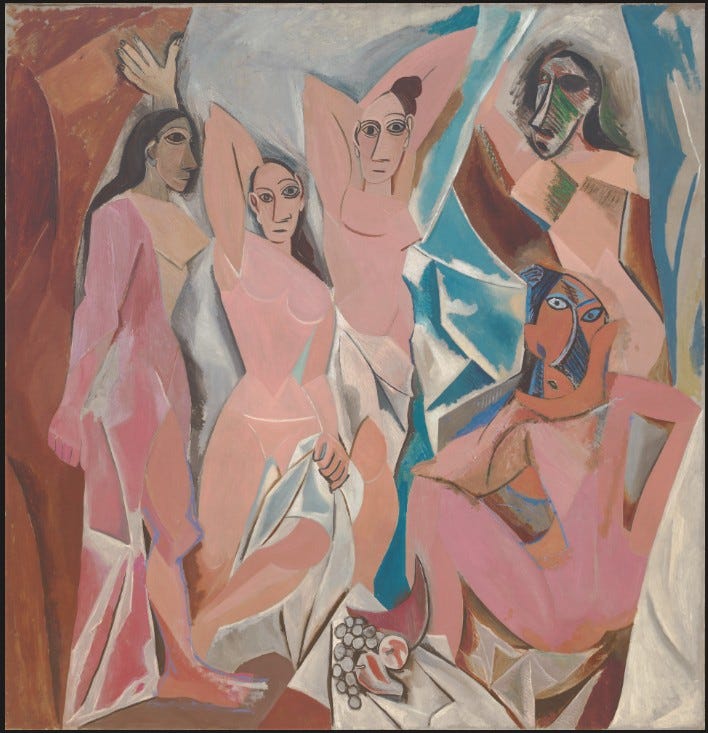

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso provoked the same indignation. The Museum of Modern Art’s 1994 casebook on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon notes that, for a moment, even Henri Matisse considered Cubism a hoax. A moment later, of course, he reconsidered and found brilliant uses for Cubist innovations. Pop Artists were called hoaxers, as were the Minimalists. The charge had acquired a patina of routine by the time the hidebound hauled it out to register their suspicions of conceptual art. By the early 1970s, some in the New York art world felt that you were not a serious artist unless members of the great, uninitiated public had accused you of trying to pull the wool over their eyes. I saw a touch of cruelty in that attitude, and yet the art in question was not a hoax. There were artists who believed that the aesthetic component of art is conceptual and therefore transmissible by way of language, with the help, if needed, of a diagram or two. Though I don’t agree, I have no reason to doubt that the conceptual artists sincerely believed in their theories of art and never intended their works as cruel tricks on a hapless audience. The intentions that drive art are generous, a truth not always obvious, even to artists.

Drunk and enraged late in the 1960s, Willem de Kooning bellowed at Andy Warhol, “You’re a killer of art, you’re a killer of beauty, you’re even a killer of laughter.” An art hoax, if any had ever been perpetrated, would have made a victim of the audience. De Kooning accused Warhol of victimizing him with art that made his virtuosity look old-fashioned. When Pop Art was new, it did have that effect. But that was not its purpose. Warhol did not intend, with malice aforethought, to make de Kooning’s oeuvre look old-hat. He intended to invent a way of making a painting that did not reduce him to a de Kooning follower. And that ambition was not cruel, as much as Warhol’s success may have hurt the older artist’s feelings—and, for a time, his market. A Warhol Marilyn is generous, for, like every other painting, it offers itself to us unreservedly, in the hope that we will see it as an opportunity to respond, to make sense of it.

Not wishing to sound too ingenuous, I should note that some artists expect our interpretations of their work to march in step with their conscious purposes or even with the doctrines that guided them as they worked. Maybe they fear the viewer’s freedom, for that is what is at stake: the permission a work of art grants us not just to make sense of it but to make of it what we will. Exercising that permission without hindrance, you find meaning not only in the work but in your experience of it. Eventually, interpretation becomes self-interpretation, as you arrive at the point of asking: who am I, who must I be to be finding these meanings here? And how do these meanings connect me to others—to the artist, to other viewers, to those who created my culture? The generosity of art is built in. It is inalienable, like our civil rights, and that is why it cannot be cruel. Moreover, its generosity is limitless, and that is why there is no end to its power to entangle us in the questions of meaning that sustain our humanity.

Having begun my career in support of the emergence of video art, I deeply identify with your concern and your thesis here. Thank you Carter. Generosity and kindness should always be central to any serious critical response to new art.

Carter, three statements in your essay triangulate for me:

1. By the early 1970s, some in the New York art world felt that you were not a serious artist unless members of the great, uninitiated public had accused you of trying to pull the wool over their eyes.

2. Eventually, interpretation becomes self-interpretation, as you arrive at the point of asking: Who am I, who must I be to be finding these meanings here?

3. The generosity of art is built in. It is inalienable, like our civil rights, and that is why it cannot be cruel.

I agree that each artist is being generous in their project, in proposing the artworks they present. But one might say the generosity of art stops when a viewer unfamiliar with its terms comes up against the hard wall of its indifference. At that point the artwork may become as neutral as the sun; its "intention" just as remote and esoteric (but without the redeeming warmth or glow). The cruelty, then, is not in the artist but in the circumstances in which the art is presented, which are often intimidating to the uninitiated. (And as you point out, even Matisse was once uninitiated to Cubism, and de Kooning to Pop.) The presumption of superiority that runs with elite viewing spaces, and the atmosphere of quiet moneyed luxury that infuses them—I would suggest that is where the cruelty lies.