At the end of “Art and War,” my October 24th post, I said that “as I continue with these essays, I will be asking directly and indirectly how making poems and paintings and other works of the imagination might fulfill a responsibility to something larger than an individual—and more substantial than some vague, transcendent notion of culture.” Since then, I’ve been thinking about the Abstract Expressionist Clyfford Still, who claimed that his art fulfilled a responsibility to something not just large but immeasurably vast.

Writing to a curator in 1959, Still railed about the shortcomings of art critics and the art-loving public, made extravagant claims for the “Vision” his paintings convey, and then issued a warning: “Let no man under-value the implications of this work or its power for life:—or for death if it misused.” Years ago, an editor at Art in America called Still’s bombast “a hoot,” a judgment most art-world denizens shared. What counted, they felt, was the formal brilliance of his paintings, not their supposed implications for life and death. But I am not so sure that we should dismiss Abstract Expressionist rhetoric as over the top or simply uncool.

If that dismissal needs an official beginning, we could find it in comments made by Frank Stella, a very cool artist—maybe the coolest of them all when he was painting the Black Paintings (1958-60) and then the aluminum and copper follow-ups. In a radio interview from 1966, Stella said that, as a student, “I had been badly affected by what would be called the romance of Abstract Expressionism … the idea of the artist as a terrifically sensitive, ever-changing, ever-ambitious person … I began to feel very strongly about finding some way that wasn’t so wrapped up in the hullabaloo.” Still’s big pronouncements about ultimate things are of course prime examples of “the hullabaloo” Stella heard as portentous noise irrelevant to what matters: purely pictorial issues.

Still’s friend, Mark Rothko, stated in 1956 that those issues were beside the point. He was not “interested in relationships of color or form or anything else.” So critics and historians needn’t turn their blinkered, specialized gaze on his paintings. Their task is not to carry out a formal analysis but to understand that he is “interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on.” More “hullabaloo.” And there is still more in Barnett Newman’s claim that if viewers could “read” his art “properly, it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.” Utopia, extreme emotions, life and death—what bearing on art do any of these have? Isn’t a painting an occasion for an aesthetic experience, a certain kind of pleasure? Yes, no doubt, but, as I wrote on October 24th, I am uneasy with the thought that there is nothing more to it, that looking at art is just a sophisticated diversion. But how do we get from an appreciation of form and color to everything invoked by “the hullabaloo”? Where do we find the something larger I have been worrying about?

Seen in a certain way, the problem of art’s larger significance is no problem at all. Many poems, novels, and paintings present themes that are bigger than any individual. Think of a poem that rhapsodizes about nature, a novel that comments on history, or a painting that promulgates identity politics. Just about any theme reaches beyond the one who takes it up. Even if you write about yourself or paint a self-portrait, your work will present your subject—namely, you—as exemplary, a topic of more than merely personal significance. Otherwise, why bother? All that is obvious, which is not to say trivial. The themes of art can be immensely important. But I am interested in something more elusive: the meaning, the value, of art considered as art—not as communication or celebration but as the realization of a medium’s potential. I’m talking about form and the difficulty of saying why it matters so much.

One intuits form’s importance, one believes that the very idea of art and culture depends on form’s successful elaboration, or one doesn’t. If one does, one’s belief may well seem sufficient. It does not, however, seem sufficient to me, though I understand how quixotic it is to try to pin down the larger significance of artworks experienced as artworks, as deployments of certain formal devices. Nonetheless, I want to see more than a narrowly aesthetic value in the beauty of a successful composition or the unity of an integrated picture plane. I want to see what Ad Reinhardt’s “art as art” means in the big picture. Of all the purveyors of Abstract Expressionist “hullabaloo,” Barnett Newman is the most helpful here, for he sketches a connection between the forms of his paintings and the political and economic meanings he claims for those forms.

In 1970, the filmmaker Emile de Antonio filmed Newman giving a monologue on an astonishing array of subjects. At the end of it, the artist returns to one of his abiding ideas:

Some twenty-two years ago in a gathering, I was asked what my painting really means in terms of society, in terms of the world, in terms of the situation. And my answer then was that if my work were properly understood, it would be the end of state capitalism and totalitarianism. Because to the extent that my painting was not an arrangement of objects, not an arrangement of spaces, not an arrangement of graphic elements, was an open painting, in the sense that it represented an open world—to that extent I thought—and I still believe, that my work in terms of its social impact does denote the possibility of an open society, of an open world, not of a closed institutional world.

When he says that his paintings are not arrangements, he means that they are not traditional compositions: pictorial images nicely enclosed by the edges of the canvas. This is true. As Newman says, space in his paintings feels “open” and implicitly infinite. From that feeling follows a larger—a more than pictorial—significance: “the possibility of an open society, of an open world.” Yes, but how do we realize that possibility? How do we get from the formal qualities of Newman’s paintings to the better world those paintings imply?

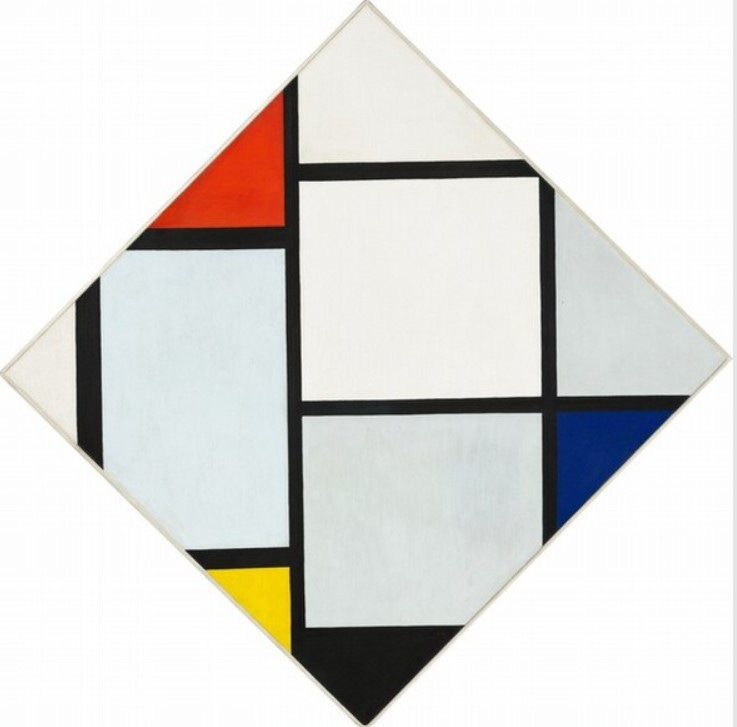

The simple answer to these questions is: we don’t. We dismiss the “hullabaloo”—the large claims certain artists have made for their art—just as thoroughly as Frank Stella did. By “we” I mean everyone in the art world, from critics and curators to dealers and most artists. Yet I wonder if the importance we grant to art might be a sign that at least some of us believe, unconsciously, that art does have a larger significance, that it might somehow exert a transformative force in the larger world. So, again, how do we get to utopia from the formal qualities of Newman’s paintings? How do we get from the “equilibriated composition” of a Piet Mondrian canvas to a “just” society, a trajectory the artist proposed in a 1919 manifesto? I don’t know. But I think we need to figure it out.

NOTES

Clyfford Still, letter to Gordon Smith, January 1, 1959. Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, ed. Clifford Ross. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990, p. 194

Frank Stella, interview with Alan Solomon, 1966. Transcript of USA Artists, a series produced for National Educational Television

Mark Rothko, quoted in “Notes from a Conversation with Selden Rodman,” 1956. Seldon Rodman, Conversations with Artists, New York: Devin-Adair Company, 1957, p. 92

Barnett Newman, “Frontiers of Space,” an interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler, 1962. Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neil, New York: Knopf, 1990, p. p. 251. See also Barnett Newman, “Interview with Emile de Antonio,” 1970, Writings and Interviews. pp. 308-9

Piet Mondrian, “Dialogue on the New Plastic,” 1919. Art in Theory: 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing, 2003, pp. 287, 288

This is a perfect introduction for your important inquiry. Is the openness of Still, Pollock or Newman akin to that of Tiepolo ceilings ?

In past eras, the inquiry was encapsulated into an established framework both in eastern and western societies. Works of Art, especially the visual ones, were categorized, or loosely organized : genre, landscape, portraits, history/metaphysical.

(TATE London publishes this--"genre is ... after history painting, portraiture, genre painting (scenes of everyday life) and landscape. Still life and landscape were considered lowly because they did not involve human subject matter.") Flowers or dead duck genres along with portraits supplied buyers with a product, often contracted and often priced upon the ingredients, i.e., Cerulean skies cost more. Portraits were bread and butter as recorded documentation of existence and authority. History subjects opened out the very inquiry of our interest, as human drama, ethics and meanings were revealed in actual events, in religious, mythological or allegorical types.

( http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/genres/history-painting.htm ).

Musical Arts had similar demarcations: scerzio, or concerto, requiem.

Literary arts too had groupings, essays, genre novels, like romance or sci-fi, historical novels or plays, like Hamlet or MacBeth, allegorical works, like The Divine Comedy.

Even today, when we go booking in a shop, we see this hierarchy again; the bookshop shelves separate our interests.

Wonderfully ! our contemporary arts explode or melt such typologies: What do we do with the van Gogh landscapes of Cyresses or the Starry Night --- landscapes for sure, but allegorical metaphysics too? , as it now seems to millions of viewers. Or, Moby Dick-- a sea novel or metaphysical inquiry? Millions read both. A Still painting is a landscape, a vision, a scope-up of paint transfigured into an allegory that the artist had the courage to name.

We sit in this undelineated situation of discerning for ourselves what values contemporary works project, how we receive and feel them, how we adjudicate them....How do we discover and then appreciate the meanings that we experience.?

In this regard, the ancient typologies may be more helpful than it might seem to the avanguardista adventurers that we are. The human dilemma of "Judgment of Paris" may offer a potent comparison of meanings found or unfound in our contemporary works.

In brief, the ethical, moral and metaphysical concerns of generations past may instruct us well in our own production, since groupings and standards are now up-to-us to decide. We went 'avant' and we have to bear up to that responsibility and measure up to the generations past, even if we would like to dodge all that.

As we reveal layers of meanings and encode them into our efforts, past achievements can provide a framework. And should !

Thank you Carter... you are creating a valuable document in this sub-stack.

John Ashbery wrote in "Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror":

That the history of creation proceeds according to

Stringent laws, and that things

Do get done in this way, but never the things

We set out to accomplish and wanted so desperately

To see come into being

If Newman did not do what he thought he did posit simply that he did do something for those who stand in front of one of his paintings for enough time. (I think of Robert Irwin in this case.) Some internal possibility. Meaning generated within an individual via interaction with an artwork, processed, passed on, absorbed in new form by others. Chaotic and indeterminate, evanescent. Not utopia or what "we set out to accomplish," but interesting and valuable.

A.R. Ammons (from Corson's Inlet):

in the bellies of minnows: orders swallowed,

broken down, transferred through membranes

to strengthen larger orders: but in the large view, no

lines or changeless shapes: the working in and out, together

and against, of millions of events: this,

so that I make

no form of

formlessness: