David Bowie: The Art of Self-Invention

Here is an excerpt from my 1983 essay on David Bowie. The excerpt picks up the story in 1976, a few years after Bowie launched his career.

In Station to Station (1976), thought and language, melody and its twin, individual gesture, are trapped by Bowie’s mastery of immobilized sound, of music so self-involved that it hovers, like a mood. The personality tries to move forward—or backward, to a belief in the lyrics’ emotionally regressive promises. Or sideways, to ironic dismissal. But the hard line laid down by the rhythm section is so aggressively circular that direction itself is elusive in the rubble-strewn landscape of Station to Station. Nothing is clear save Bowie’s refusal to perform, to give in to melodic impulses, to try to sing a song or devise a self, except under conditions that make these efforts nearly impossible. And the damaging milieu must also be of his own devising. Otherwise the fragments of the self that emerge would count only as the helpless products of uncontrollable forces.

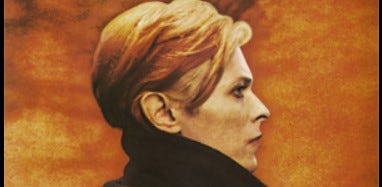

To ask why Bowie doesn’t skip all this fuss and go for melodic clarity is like asking why Kurt Schwitters didn’t sweep away those bits of rubbish and find himself a sharp pencil and a clean sheet of paper. When the question of coherent form—or an integrated self—appears under pressure from a disintegrating culture, the most courageous attempts at an answer take those pressures into full account. The self must acknowledge, not deny, them, or so many in our era have thought. Popular entertainment usually offers censorship-as-culture, with the help of an image-machine that grinds out simulacra of acceptable selves for mass consumption. Bowie enmeshes himself in the machine, then extricates himself by remodeling its workings. He escapes into his isolation, his integrity, with the help of personae recruited from the culture’s peripheries—among them, the androgynous, glittering Ziggy and the black-suited hero of Station to Station, a figure whose chilly elitism would not have been negotiable before Bowie repositioned him. Assuming a place above but never apart from Pop culture, Bowie denies himself the “high-art” stance from which one dismisses the mass audience and thereby claims an automatic integrity. He has chosen to operate in those zones of the culture where no such delusions survive. Bowie cares only about the self he constructs as he struggles with market forces that construe selfhood as a manageable nuisance.

On Heroes (1977), the will to detach song from sound is more powerful than it is on Low (1977), but in a dubious way. The lyrics, melodies, and tempos on this album’s cuts show the fierce energy of desperation, of hopeless and grandiose theatricality, that was eminently salable in the late 1970s. The clenched-up, hard-rock rhythm goading each track on Side A of Heroes (the instrumentals of Side B answer those on Side B of Low), endlessly repeats its promise of forward motion, of an advance toward resolution. But the electrometallic buzz wins out against these hopes, this theatrical yearning. In the title song lyrical passion ends up as the grandiloquence of automatons. The crooning, croaking character who claims that “we can be heroes, just for one day” turns out to be an early glimpse of the “Little metal-fated boy . . . so war-torn and resigned” of “Because You’re Young” (Scary Monsters, 1980 ). Robert Fripp’s contribution is a torrent of frantic guitar chords into which he manages, astonishingly, to insert high, delicate, glittering accents. These float clear of the album’s electronic hurricane, but they have nowhere to go. So they’re drawn back into the storm, the atmosphere against which Bowie is testing himself. Fripp disappears into a landscape largely of his own making, but one willed by Bowie, the producer.

Bowie is never satisfied simply to intend an image. He must make its intendedness icily clear. So his music permits no question of the improvisational union, the warmth, that generates the image of working together that rock musicians hold out as an ideal (whatever the facts of studio production). Bowie’s vision is openly hierarchical; rather, his imagination is so thoroughly engaged in manifesting itself to itself that he cannot conceive of the world save as the structure he ascends to arrive at his imagination’s isolated preeminence. His career began at some point beyond the shame he might have felt about this, and now, wandering in a seigniorial state, he possesses a kind of generosity. Having learned hard-rock rawness from Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, Iggy Pop, and Mott the Hoople, Bowie paid his debt by producing records for them (some in 1972–73, others in 1977). It was as if the Stones helped Muddy Waters put out a record—star lends grateful hand to major sources. Iggy Pop was desperate at the time, and he got the most help. Bowie produced three of Iggy’s albums, wrote most of the music on Lust for Life (1977), and put in a stint at the keyboards during the Iggy Pop tour of 1977.

The Idiot (1977) and Lust for Life are authentically harsh and desperate tours de force. And Iggy Pop ended up a puppet, his strings pulled never more deftly than in those passages where he is at his most inventive. Pop presents himself on the cover of The Idiot in a marionette’s pose, disjointed and apprehensive. The image is a reprise of the marionette as crooner, grand and unbelievably passionate, on the cover of Bowie’s David Live (1974).

All of Bowie’s gestures permit satirical readings, most of which are dead ends. The 1970s were the years when put-ons and put-downs, send-ups and take-offs taught commercial entertainment to recycle its images faster than ever before. Ironic distance is now a leading commodity on network television, a counterpart to the newsroom’s “objectivity.” Still, to see Bowie’s ironies as highlights of an ironic era would be to lose him in the image-shuffle. Granted, he plays at getting lost in just that way, but the point is to see how he wins the game—how he emerges from the labyrinth intact, held together by a new, necessarily contingent vision of what it might be to assemble one’s integrity in the light of all that mitigates against it.