Here is an excerpt from an essay I published in 1991, in Artforum.

Fashion is ephemeral. Those who are concerned with fashion have a motive to deny this, to say, no, you don’t understand: of course it is true that clothes are different every year, for it is only through change that standards can be maintained; only by shifting restlessly, alert to the world’s alterations, can the ideal of timeless elegance manifest itself in the new season, now, at this instant. Those who are concerned with fashion also have reason to agree that it is ephemeral, to say, yes, how could it be otherwise: of course clothes have a fresh look each year, for only by renewing itself can fashion preserve its allure; only by reflecting and brilliantly transmuting the churning, shapeless patterns of the ordinary can elegance stay alive, now, at this instant.

Swirling in distracted circles, talk about fashion tends to arrive, if only for a moment or two, at absurd conclusions: fashion changes and it doesn’t change; or it changes but only to sustain the eternal; or the nature of fashion has undergone deep shifts in recent decades, yet its changes still follow tight patterns that are themselves changeless; or—whatever. When I talk about these matters to fashionable people or to people in the fashion business (groups whose boundaries are not identical), the conversation soon gets to whatever. After all, the fashion world runs on intuition, not on critical rumination.

A passionate involvement with fashion requires one to register the subtlest of hunches. One must make judgments, the more daring the better. But one must avoid—better, one must abhor—any analysis of fashion, for nothing is less fashionable than that. Granted, semioticians, structuralists, and deconstructionists have subjected fashion to their various methods, but their conclusions have no weight in the circles occupied by designer Christian Lacroix, designer-photographer Karl Lagerfeld, or John Fairchild, the publisher of Women’s Wear Daily. In academia, the various styles of theoretical analysis have their own chic, which receives no closer scrutiny on campus than the chic of a new look receives in the pages of WWD. Chic wards off analysis with a flair that prompts a definition: the chic is that which devotees find so overwhelmingly alluring that questions about its allure cannot be formulated.

Accused of chasing after intellectual fashion, deconstructionists say the charge is unfair: one deconstructs because it is one’s scholarly, even moral duty to do so. The defense of the fashionable is always sanctimonious, whatever the target being defended—an academic method or a hemline. And there is much sanctimony in our culture, for we judge much by fashion’s standards: sneakers, neighborhoods, cuisines, slang, and so on. Yet only fashions in expensive clothing count simply as fashion. These clothes give the subtlest, most powerful form to the inanity that makes every fashion so questionable and so seductive, therefore so good at discouraging questions. Because the notion of timeless timeliness is obviously silly, fashionable conversation avoids the topic. Because it is the product of concepts mishandled, a timeliness untouched by time is difficult to render as a visual image. Yet the feat has been managed.

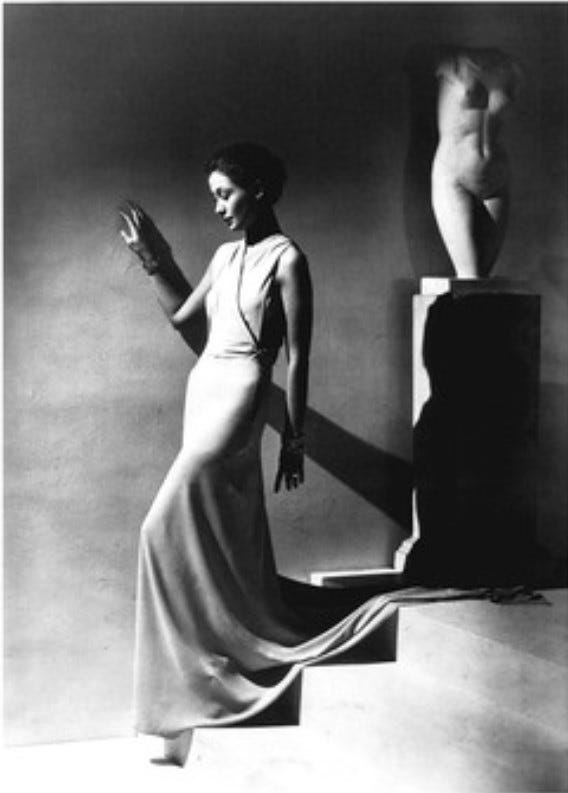

In 1934 Paris Vogue published Baron George Hoyningen-Huene’s photograph of a woman in an evening dress walking down three steps. As she extends her left foot toward the floor below, the train of her dress trails up the steps she has just descended. The tilt of her head, the arch of her eyebrows, the serenity of her downward gaze, the contrapposto she achieves with her elegantly slung right hip—every detail of her image announces the certainty of the equilibrium she felt the moment the shutter clicked. It is with casual irony, therefore, that she extends the fingers of her right hand to the wall beside her, as if to steady herself. Behind her, on a pedestal, stands a three-quarter-length statue of a nude female body. Its head and arms are missing. It looks classical at first glance, and, at second glance, faintly Deco. This figure, too, is nicely balanced. Observing a contrast, Hoyningen-Huene has drawn an equation.

The contrast is between a human form that is living and one that is not. This difference is great, and so are the similarities that mitigate it: the balance, the clarity, the voluptuous calm, the authority displayed by both forms, the fleshly and the statuesque. This play of contrast and sameness appears in several other fashion photos Hoyningen-Huene made in 1934. One of them shows the head of a generically classical male figure, probably of plaster. He looks to the right and downward. In front of him stands a female model. She brings an ocular equipoise to the image by gazing upward, to the left. Another shot from that year shows two female models in gowns. One sits and the other stands. Behind them a column rises, topped by a fragmented, armless torso of a man. Their chic is absolutely fresh—one could say crisp—and all the more assertive for being understated. Yet it offers no reproach to the aura of timelessness, of the eternal, given off by the unclothed statue.

The photographer induces opposites to get along so well that they appear to set aside their differences. Classical form—or at least form with an air of Mediterranean antiquity—begins to look stylish, up-to-date, fashionable. The forms of high fashion assume the look of the statuesque, the hallowed, the ageless. Living flesh has the smoothness, the soft luster of ancient marble. Stone, it almost seems, is as supple as flesh. Hoyningen-Huene makes an equation between living and not living bodies, and the equation enchants, for in his photographs the bodies that do not live are not dead. They are statues. His imagery argues that in the realm of fashion there is no death. To inhabit the fashionable instant is to live forever.

'To inhabit the fashionable instant is to live forever.' You touch upon the instinct of living beings, that of inhabiting the instant with vitality. Yet, those conscious of outward appearance and their fashionable moment want to draw attention to their visual appearance. Why is some of that appearance deemed timeless ? Yes, when there are classical comparisons to balance, harmony, reserve and calm, values that have proven worthy over millennia, the visual appeal claim is timeless. But, there are other values in fashion too, such as verve, pizzazz, or freshness. How about sexy ! Certainly, being alive, we wish to feel like we live forever and appreciate the phenomenon. Visual arts

give us those insights too, in different ways.

Can we wonder about the frequent combination of visual art and visual fashions and the underlying values involved in both ? I submit that both generate meanings and values that overlap. I love fashionable people my exhibitions. It feels more vibrant and intense and many of those people are interesting in themselves. But beyond that utility, high visual art reveals metaphysical values and meanings however unique to our times that are poignant to all times: the fundamental contemplations about being human. High visual fashion brings to mind values of our immediate being, like verve or calm and harmony. Both these expressions show us into our human qualities and compliment one another. This is why those photographs seem so right, so normal: the sculptural forms and evening gowns belong together, as they so often do go together.

NOTE-- The granite forms last longer than the wool and silk, and I suggest that high visual art conveys more poignant metaphysical meanings than high visual fashions.