In 2003 I published an essay on the art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe. The following excerpt focuses on the art critical comment prompted by the work she exhibited in the 1920s. As you’ll see, the commentators were all male. I lead into the subject with a quick comment on the photographs of O’Keeffe taken by Alfred Stieglitz, her husband and most fervent admirer.

Stieglitz’s photographs of O’Keeffe show her full length and in detail, from a point of view at once dignified and adoring. O’Keeffe is simply dignified. These images now look like collaborations between equals, though they do not seem to have been understood that way in 1921. The critics’ response to O’Keeffe’s exhibitions of 1916 and 1917 had given her the aura of a woman determined to confess her sensuality. Here, in these photographs, gallery goers saw this famous woman in the flesh. Early in 1923, an exhibition of her work opened at the Anderson Galleries. Organized by Stieglitz, it contained nearly 140 oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, and drawings. This show made O’Keeffe an icon of the liberated 1920s.

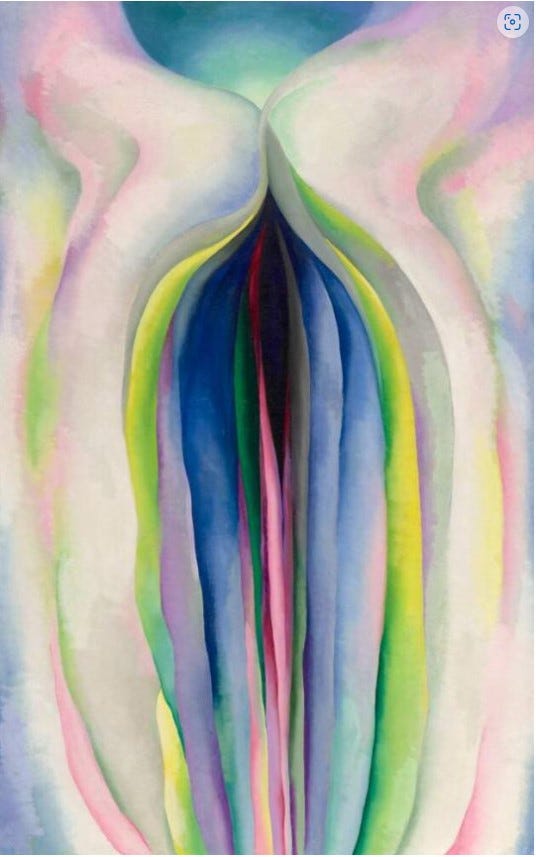

From 1912 until 1914 she had served as a supervisor of drawing and penmanship in Amarillo, Texas. Some of the paintings in the Anderson show alluded to the west Texas plains. Others pictured what the artist called the “little, pretty scenery” around Lake George, New York, where she had lived with Stieglitz in his family’s summerhouse. Often, landscape gave way to still life or imagery at the scale of the body viewed up close—or felt from within. The exhibition’s allusive sweep excluded little but the architecture that would preoccupy her toward the end of the decade. We can’t know, of course, what caught the public’s attention. We can be certain, however, that writers focused on the artist’s most lavishly corporeal images.

O’Keeffe “painted with her very body,” declared Alexander Brooks, in The Arts. Painting is a physical activity, so all painters paint with their bodies; but this is a literal truth, and Brooks was getting at something more theoretical—indeed, metaphysical. An implication of his remark is that male artists exercise judgment as they work; no matter how powerfully intuition may drive them, their inherent rationality stays in control. Brooks saw O’Keeffe, by contrast, as the medium of feelings and physical intuitions over which she could not possibly have any command. She is passive, a sexually charged recording device, as Herbert Seligmann suggested by explaining that her landscapes look the way they do because “her body acknowledges its kindred shapes and renders the visible scene in those terms.” Because she is a woman, O’Keeffe is not in the world as men are; or women are not in the world at all, for they are part of it: femininity as Nature. Seen this way, a female painter is not so much an artist as cunning Nature’s way of getting some of its shapes imprinted on canvas.

Barbara Buhler Lynes, author of the O’Keeffe catalogue raisonné, has traced the language of such critics as Brooks and Seligmann to figures in Stieglitz’s circle—Marsden Hartley, for example, who wrote in 1921, “With Georgia O’Keeffe, one takes a far jump into volcanic crateral ethers, and sees the world of a woman turned inside out.” Her art is confessional, but with no moral significance, for what she confesses is her womanhood: a state of passionate physicality usually hidden by social niceties. The paintings and drawings of O’Keeffe, said Hartley, “are probably as living and shameless private documents as exist.” Another friend of Stieglitz, the writer Paul Rosenfeld, declared that O’Keeffe’s “art is gloriously female. Her great painful and ecstatic climaxes make us at last to know something that man has always wanted to know.” By quoting this sort of thing in brochures circulated under his gallery’s imprimatur, Stieglitz helped it to become the stuff of popular journalism. And it was Stieglitz who guided Hartley, Rosenfeld, and other colleagues to their view of O’Keeffe as an art-world Salome, the painter who removes the ultimate veil from the nature of femininity—or from Nature, which is feminine and blind, in contrast to the male and all-seeing critical mind that enunciates the Truth about art.

Stieglitz saw O’Keeffe as “the Great Child pouring out some more of her Woman self” in each of her works. The core of that self, Stieglitz believed, is the womb. A certain logic is implied: if the anatomical part that defines an individual as female is “the seat of her deepest feelings,” her individuality is null, for she is a function of the flesh. Instinctual and unthinking, she is to be praised as one might praise a fine physical specimen. Male in fact or in attitude, the critical gaze found in O’Keeffe’s early works a wanton evocation of breasts and buttocks and vaginal labia—or of some, vague, elemental vitality. “There are canvases of O’Keeffe’s,” wrote Paul Rosenfeld, “that make one to feel life in the dim regions where human, animal, and plant are one, undistinguishable, and where the state of existence is blind pressure and dumb unfolding.”

Of Rosenfeld’s writings, the artist said simply that they “embarrassed” her. Generally, the critics left her “full of furies.” Yet these writers, spurred on by Stieglitz, had made her famous. What was her complaint? O’Keefe’s fury baffled Stieglitz and his colleagues because they saw themselves as progressives who had reversed the usual valuation of men and woman: a hierarchy had been equalized. Stieglitz declared, “Woman can only create babies, say the scientists, but I say they can produce art, and Georgia O’Keeffe is the proof of it.” Women are more physical than intellectual, more intuitive than rational, yet they too can be artists. The age-old understanding of femininity is not wrong, according to Stieglitz; all that needs to be corrected is the male of judgment of female capabilities. O’Keeffe understood this reversal, but she was not appeased. Friendly or unfriendly, traditional ideas of femininity are insulting, annihilating, and O’Keeffe rejected them utterly.

Stieglitz is remembered as a hero of American modernism, so it may be surprising to recall the things he and others in his circle said about O’Keeffe and women generally. Surely the art world, at least, has gotten past the notion of women as the irrational counterparts to men, who embody the very spirit of rationality. Perhaps it has, though I think that not much has changed during the past century. No one today would describe a woman in terms anything like the ones that Stieglitz, Rosenfeld, and their colleagues used to describe O’Keeffe. Nonetheless, many men preserve our culture’s archaic assumptions about women.

Thanks. The message is unfortunately much needed and relevant a hundred years after O'Keefe.

In 1985 my book The Art & Life of Georgia O'Keeffe came out. Maybe you saw it or read it or just used my title by accident? I wrote about O'Keeffe's language of forms, her reception by male critics and artists in her circle, and more. Your perspective never goes beyond her reception. Cheers, Jan Castro