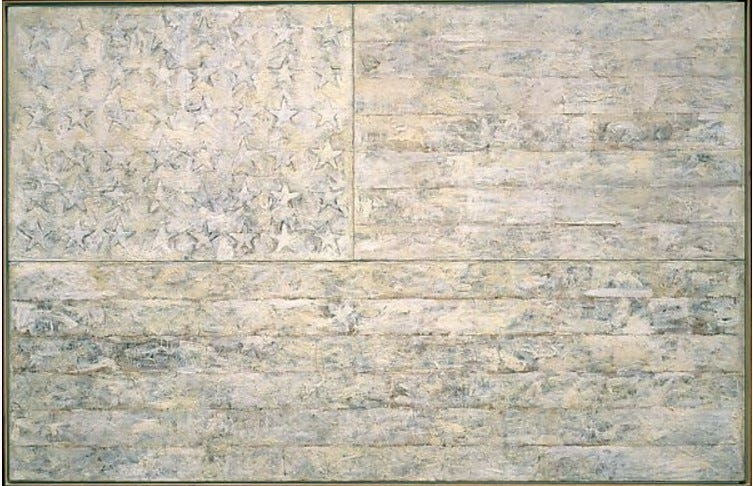

In the only dream he ever recounted, Jasper Johns saw himself painting the American flag. Having dreamt it, he did it. Flag, 1954–55, is five feet wide, its stars and stripes meticulously rendered in encaustic, a medium consisting of beeswax melted and mixed with pigment. After the mid-1950s, Johns usually worked in oil paint or acrylics, and yet he returned to encaustic now and then, most notably in the Crosshatch paintings that preoccupied him during the 1970s. Quizzed about his preference for a medium that has been employed by very few painters since medieval times, Johns said he likes it because it makes a precise record of each touch of the brush. “It drips so far and stops,” he added. “Each discrete moment remains discrete.” This desire for control was remarkable in a time when Willem de Kooning’s brushwork and Jackson Pollock’s drip method were merging colors in surging, improvisatory currents. Their imagery was hot. Johns’ was cool. More than that, his paintings had a disquieting air of pensiveness.

In his early work, Johns did not impose a strict order on the rambunctious energy of the Abstract Expressionists so much as confine it to the linear patterns he found readymade in the American flag, the concentric circles of his Targets, and the repetitive angles of the grids through which he sent numbers and letters marching, zero to nine and A to Z. Traditionally a sign of sincerity, painterly painting acquired from Johns a tone of skepticism. The AbEx claim to heroic self-revelation vanished under a patina of irony. Yet we are not put off by Johns’ elusiveness. On the contrary, his sphinxlike presence in his art has exercised a persistent fascination, in part because it conveys a peculiarly American way of being—one of which certain artists and writers have long been aware, if only intuitively.

In Henry James’ case, of course, this awareness was hyper-conscious. James’ lengthy appreciation of Nathaniel Hawthorne, published in 1879, makes the point that the earlier novelist’s milieu was not as rich, not as dense with historical and social complexity, as that of his French or English counterparts. In America, wrote James, “The very air looks new and young; the light of the sun seems fresh and innocent, as if it knew as yet but few of the secrets of the world and none of the weariness of shining.” Like his friend, the painter John Singer Sargent, James was more at home in the labyrinthine subtleties of European society than in the improvised openness of American life. By contrast—and this is a contrast as consequential as the one that sets the agrarian Thomas Jefferson at odds with the mercantile Alexander Hamilton—Hawthorne felt at one with that openness, rife as it was with possibilities traceable to early American roots. Viewing the Old World with bemused detachment, he was a model of tolerance in comparison to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who expressed irritation at what he saw as the impacted stasis of Europe. The Grand Tour of its cultural monuments, he felt, is only superficially interesting; one’s time would be better spent by staying at home and cultivating one’s unique and inimitable self. The goal is to find “an original relation to the universe,” as Emerson put it in the introduction to Nature, his still-daunting essay from 1836.

Accepting no mediation from history or tradition, indifferent to cultural norms and social expectations, one creates one’s place in the world from insights prompted by the flow of personal experience. In the process, one creates oneself. Viewed soberly, this is dubious. We cannot, after all, step outside the culture to which we owe the ideas of self and originality. Illogical as it may be, Emerson’s exhortation is still stirring, especially in America, where belief in the possibility of thoroughgoing self-invention remains strong. Call it the Gatsby Syndrome. Turning to postwar American art, we see Jackson Pollock revising utterly the very act of painting. Removing what he called “the eyeglasses of history,” Barnett Newman saw his way to a radically new concept of geometric abstraction—one that extricated painting from the constraints placed on it by Piet Mondrian, who played in Newman’s scenario the part of an Old-World oppressor. To be American is to be free. By painting the American flag, Johns claimed that freedom for himself. Moreover, he joined Pollock and Newman and a few others in the small band of artists who can be said to have achieved an Emersonian degree of originality.

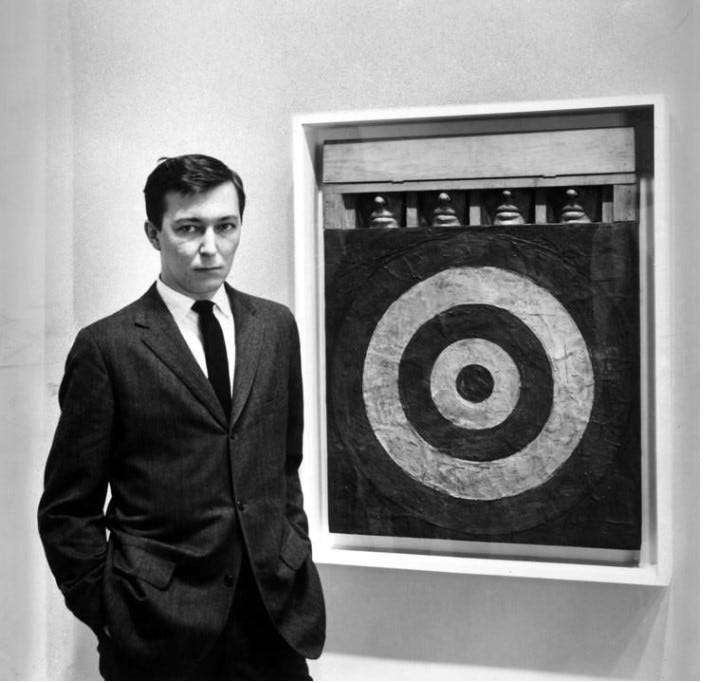

In 1958, Leo Castelli gave Johns his first solo exhibition. With its encaustic Flags and plaster faces and body parts lurking in compartments above deadpan Targets, the show was that year’s sensation. Johns became the artist about whom it was necessary to have an opinion. Detractors saw him as an upstart bent on undermining everything passionate and authentic. Admirers were enchanted by all that surprised them in his paintings—the unapologetic banality of their motifs, the geometric rigidity of their structures, the rubbery elegance of their surfaces. Casting about for a label to apply, Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art came up with “Neo-Dada.” Like Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and other Dadas, Johns introduced the mundane into the realm of high art. Like them, he devised odd juxtapositions. But the label didn’t stick.

The spirit of Dada was antic. Johns was calm, disquietingly so. The Dadas were in revolt against the past, bourgeois respectability, even art itself. Immersed in his own subtleties, Johns could not have been less militant. Turning inward, he had achieved at the age of 28 a full measure of self-reliance, that Emersonian virtue; and this gave him an “original relation” not to nature but to art. In the decades since then, no one has tried to corral him in a stylistic category. Johns stands alone, distant even from the many artists who have borrowed and revised his strategies.

Among the most salient examples are Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and other Pop artists who learned from Johns that art has a place for the readymade iconography of the supermarket. Before there was a Campbell’s Soup Can by Warhol there were Johns’ three-dimensional renderings of a Savarin Coffee can and two Ballantine Ale cans, both from 1960. Lichtenstein’s comic-book images of love and war were preceded by Johns’s Alley Oop, 1958, which deploys a field of orange paint as a backdrop for a multipaneled page from the comic strip by that name. Alley Oop and the other characters are masked by touches of paint that set them adrift in a border region between the abstract and the figurative. Dispensing with these ambiguities, the Pop artists opted for sharp edges and inflected patches of color. So did the Minimalists, whose further borrowings from Johns included grids, symmetries, and the literalism of his early sculptures.

The quasi-Minimalist patterns of Frank Stella’s black stripe paintings evolved directly from the red and white stripes of the Johnsian Flag. And Brice Marden’s early monochromes reprise, with slight shifts in hue, the blank passages in Johns’s early gray paintings. By the end of the 1960s, Johns was recognized as the era’s most influential painter, for he had established for that moment the look of serious art. This authority was unsought and of course many resisted it, yet the New York art scene of the following decade was crowded with newcomers performing ham-fisted variations on Johns’s sooty, ruminative brushwork. His influence did not, however, make him a chef d’école. Though there has always been much for other artists to learn from Johns, he has never displayed a teacher’s approachability. Artists must borrow from a distance, across the immense gap that separates his sensibility from theirs. It is possible to paint a Picassoid painting or de Kooningesque painting, but only Johns can paint a Johnsian painting.

Presiding over a landscape we cannot imagine sharing with him, a Flag by Johns is the symbol of an America of his own devising, a New World populated solely by him and built in part from old-fashioned objects and logos and typefaces recalled from his childhood in South Carolina. Thus, Johns takes his place in our imaginations by occupying a place far from the rest of us but very near our ideals of self-sufficiency. He exemplifies American independence.

Your ability to weave so many relevant views about an artist's work continuously expands my appreciation of your insights

This is a wonderful and insightful review.

Indeed, that petulant bystander of the American experience is so unique. The same petulance extends to painting itself, to its colors and structures; droll and coy are his depictions. To this day, no one can pin that down... Come on Mr Johns : YEA or NAY ! ....( silencio )

I feel this same disquieting observation without judgement in the early Warhol works, particularly the silk-screen "Car Crash" and "Jackie" pieces. Both artists are asking us to witness, just witness. Imitators and followers lack this suspension of judgement, this quietitute; those others have opinions and force viewers to see it their way. The Artists Johns and Warhol leave our own experience free and unattached from the directives of the painter.

Here, we encounter the field of 'meanings and interpretations over eras' that your essays reveal. For centuries, viewers will look at these images with openness and freedom to interpret, as presented by the Artist. This freedom is the very core of the American Experience , the directive from Emerson, "an original relation to the Universe."

Yet again, another American Artist found his way to it and has trapped future viewers into that droll, coy enclosure.

Mr. Johns is still living peacefully in the Caribbean, so tribute and praise to him.