The filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt once told me that when he came to New York, in the 1930s, soot piled up on windowsills like black snow. Furnaces burnt coal in those days, and its residue was everywhere. I saw metaphorical traces of it in paintings by Franz Kline, in Attic, 1949, and other black-and-white pictures by William de Kooning, and in Jackson Pollock’s denser canvases. That sootiness reappears in early work by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who were determined not to be acolytes of Pollock, de Kooning, and Kline but made no effort to rid their art of Abstract-Expressionist grittiness and griminess that signifies New York.

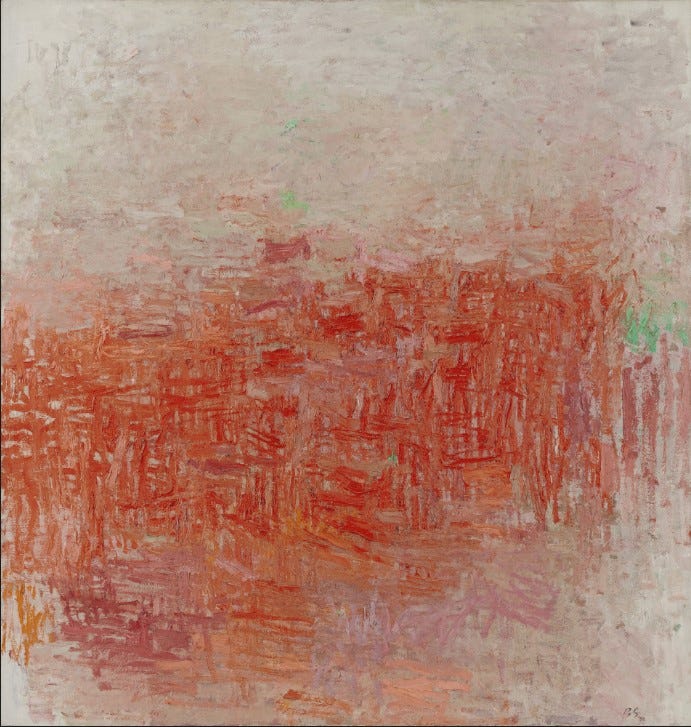

Not all the Abstract-Expressionists let the city tinge their paintings. Mark Rothko’s rectangles of color are not sooty, even when they are dark. After he hit his stride, Barnett Newman filled his large canvases with sheer luminosity. You see a more nuanced, more intimate light in Philip Guston’s paintings from the 1950s. In 1955, Thomas Hess, the editor of Art News, named two exemplars among the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. One was Willem de Kooning, who served as a father figure for Grace Hartigan, Alfred Leslie, and a slew of second-generation AbEx painters. The other was Guston, who stood at the center of an inter-generational cluster that came to be known as the Abstract Impressionists. Beside such non-figurative painters as Joan Mitchel and Rosemarie Beck, this group included Nell Blaine, Robert De Niro, and other depicters of things. Uniting these artists was a shared tendency toward subtly shimmering textures of high-keyed color.

Guston’s textures were the subtlest, the most glowingly textured of all. Then, in 1968, he exchanged his elegant and influential manner for a deliberately crude, cartoonish style that made R. Crumb look, by comparison, suavely refined. Astounded, the art world wavered between dismay and outrage. A great painterly style had suddenly vanished, and Guston’s subjects made matters worse: drunks surrounded by empty bottles, heaps of dismembered legs, hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan. Despair, modulated only by fear, now pervaded Guston’s world.

His later works are difficult for contemporary curators. In 2020, soon after the murder of George Floyd, the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, announced a four-year postponement of its upcoming Guston retrospective. The museum’s staff and board of trustees explained that the racial tensions then wracking American society would render his pictures of Ku Klux Klanners “incendiary.” Their explanation is understandable if not convincing. Some of Guston’s later work would be incendiary if his mockery of the Klan and his condemnation of racism were difficult to perceive. But they aren’t. They’re obvious, or so it seems to me. Anyway, the period of postponement was shortened, and late in 2022 the Boston Museum of Fine Arts opened its doors to the retrospective, which then traveled to the National Gallery and two other museums, receiving rave reviews at every venue.

I have been thinking about all this because I recently ran across Rene Ricard’s review of a Guston exhibition in a 1978 issue of Art in America. The show, at the David McKee Gallery, presented drawings from the 1940s to the end of the artist’s career, in 1980. Working in ink on “brownish” paper during the 1950s, he made what Ricard called “brushy bouquets”—black-on-off-white counterparts to his lush Abstract Impressionist paintings from that decade. Then came 1968 and the appearances of Guston’s “loonies,” as Ricard calls them.

“They stare at their naked light bulbs,” the critic writes, “and try hard to figure them out. But you know they aren’t going to get anywhere. Or a head lies on a table with a bottle and you know that bottle has more going on inside.” Ricard says he looked more at the cartoonish drawings than at the “lovely” ones from the ’50s, even though he “liked” the latter more. Next, he poses a good question. “What, after all, is so important about ‘liking’ art?” Not much, he implies, and I agree.

I like pistachios and spaghetti puttanesca. I like certain shows on Netflix and detective stories by Dick Francis. I like things that are pleasant or diverting or both, but I would never say that I like the Sistine Chapel ceiling or Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm, 1950. And did anyone ever say, “I highly recommend James Joyce’s Ulysses. I think you’ll like it.”? It would make more sense to say, “I think you probably won’t like it, it’s too complex to be likable, but read it anyway. The book is powerful and worth the effort.” Here you might say, “Just a minute, I like powerful works of art—Hamlet, Guernica, Philip Guston’s grisly tableaux.” All right, but there are several varieties of liking.

There is the kind that prompts one to say one likes the way an abstract painting goes with the upholstery on the sofa beneath it. This is much the same as saying that a certain tie matches a certain jacket or this cheese complements that Bordeaux. Whatever pleases is likeable, which is fine, as far as it goes. Beyond that sort of liking is the kind inspired by a painting or a poem that confronts you with its significance—that has an important, possibly difficult meaning, and challenges you to grapple with it. We do not merely like a work of that kind. Rather, we care about it in a way that is hard to distinguish from caring about oneself, about others, and about the world.

Not long after Klansmen and hopeless drunks made their debut in Guston’s art, he invoked “The [Viet Nam] war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world” and then asked, “What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue? I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.” There comes a time when one wants what one does to address the world beyond the haven of one’s sensibility. Whether making a work of art ever counts as doing something about “the brutality of the world” is a question that may be unanswerable. Serious artists are those who carry on as if they knew that the answer is yes.

Thank you for this. The ending paragraph is sticking to me 💭

This is the heart of the whole “thing”. ❤️