Sol LeWitt’s “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” 1967, contain this: “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art … the idea becomes a machine that makes the art. This kind of art is not theoretical or illustrative of theories; it is intuitive, it is involved with all types of mental processes, and it is purposeless.” LeWitt was a notable innovator and his most complex works still have the aura, however dispersed by time and faulty memory, of the new and unassimilated. But his idea of “purposeless” art is as old as Kantian metaphysics.

In his Critique of Judgment, 1790, Immanuel Kant says that beauty is the quality that “pleases apart from any interest.” We like a beautiful thing—a sunset, a flower, a painting—in and for itself, apart from any use we might have for it; and if you feel that the beautiful thing has the unified, coherent form of something useful, something made for a purpose, you have set yourself up for the challenge of wrapping your head around one of Kant’s wonderfully paradoxical turns of phrase: “purposiveness without purpose.” (Zweckmässigkeit ohne Zweck.) According to Kant, the beautiful thing refuses to be swept away on the currents of utilitarian life.

The Earl of Shaftesbury floated the idea of a disinterested contemplation of beauty in Characteristics, 1711. Between his time and Kant’s, a number of other writers joined the discussion, but I don’t want to get too archeological. I only want to point out that in modern times (the era launched by industrialization, ornamented by the bourgeoisie, and punctuated by revolution) the notion of the beautifully useless or uselessly beautiful object has been available to anyone who could find a use for it.

The opposite notion has been around for much longer. The Roman poet Horace said that poetry should “instruct and delight.” This is known as the Horatian platitude, which the poet Philip Sidney repeated centuries later. And if no one repeats it much anymore, the axiom that literature should be instructive continues to guide most book reviewers. Why take the trouble to read a serious novel if you’re not going to get something useful out of it? Not every modern sensibility has wanted to cultivate Kantian disinterest. But some have.

The clamor for morally instructive fiction so exasperated Théophile Gautier that he prefaced his 1835 novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin, with a diatribe culminating in a grand principle: “There is nothing really beautiful but that which is useless.” Between Gautier and Sol LeWitt is a milling crowd of aesthetes, among them Walter Pater, who recommended in 1868 a “quickened, multiplied consciousness.” The most reliable way to achieve this exalted state, Pater explained, is to cultivate “the poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for art’s sake … for art comes to you professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.” In “The Function of Criticism,” 1923, T. S. Eliot was more concise: “I have assumed as axiomatic that a creation, a work of art, is autotelic”—of value in and as itself, not as a means to an end.

Like the principle of freedom, the ideal of art unsullied by usefulness is subject to endless reformulation. “There is a pure art, solely concerned with realizing itself,” wrote the littérateur Remy de Goncourt in 1900, adding that “no definition can be given of it, as this would be achieved only by associating the idea of art with ideas that are foreign to it and would tend to obscure and dirty it.” The idea of art interested only in “realizing itself” gets recycled in Clement Greenberg’s supposedly Kantian idea, set forth in 1960, that “each art had to determine, through operations peculiar to itself, the effects peculiar and exclusive to itself … Thereby each art would be rendered ‘pure,’ and in its ‘purity’ find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as its independence.” The artwork’s purity grants it independence and its independence certifies its uselessness for anything but aesthetic contemplation. But isn’t aesthetic contemplation in some way useful? If it were not, would so many sophisticated writers have recommended it?

I think there are two uses for uselessness. The first takes us into the realm of symbol, where the pure, disengaged, autonomous work of art stands for the autonomous individual. Ordinary life is a practical matter of means and ends, of “getting and spending,” as William Wordsworth puts it. The trick is to disentangle ourselves from these utilitarian activities, whereupon we will step free in the character of our true selves, undistorted by the world’s expectation that we be of some use. “The notion of being a useful person has always struck me as quite hideous,” wrote Charles Baudelaire in one of his notebooks. Opposite the useful person stands the Baudelairean dandy, an exquisite creature self-fashioned from his own refined tastes and predilections. The ancestor of Parisian personage is Beau Brummell and his heir is Oscar Wilde. As important as these figures may be in the history of modern culture, their adamant dismissal of any social or ethical considerations raises objections both unavoidable and too complex to examine here in any detail. But just ask yourself: would you really want to have anything to do with a person devoted solely to his aesthetic perfection?

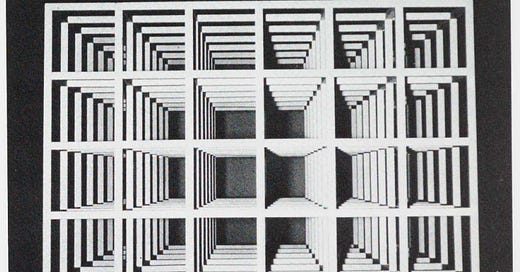

The second use for uselessness emerges when we set aside the absolutism of the dandy and the hardcore aesthete—when we allow, for example, that a grid by Sol LeWitt has no purpose comparable to that of an electrical grid and yet is not just a pure form encapsulated in its purity. Reaching beyond itself, a LeWitt grid alludes to its maker, to architecture, to traditional perspective. It engages us, if we let it, with intricacies of form that may well lead us to reflections on our looking, our seeing, our capacity for making sense of things. Thus it has, in its austere way, the social, even ethical purpose of launching an interchange, a conversation, which generates the sorts of meanings that join us to a culture. None of these effects result from a conscious, purposeful program. They follow from intuitions, from trains of thought and feeling that remain largely unconscious. Yet these elusive effects are purposeful and occur only when artists exclude from their works the ordinary, all-too-obvious purposes that Kant and Gautier and the rest of that high-minded band found so objectionable.

There is no way out: you keep pointing at the core of the artistic quandariies of our time. I’ve sent this one to my students at MICA in Baltimore. And I cant resist commenting, hope not to be a bore.

Picasso apparently asked how is it that when several artists “do the same thing, only one, perhaps two, make good art?”

It raises the usual haunting Q question: what is good art, how is Quality measured?

To defend the legitimacy of purposeless art is important. I am among the legions of art people defending that belief. And you are arguing on its behalf in your usual brilliant and understated way.

But I wonder if there isn’t a shadow issue hiding behind these discussions.

And I have no clear answers to a flood of questions I get nervous about.

Why should Quality not happen also in art that is applied to a purpose?

And if targeted art is OK for me, even though I avoid it, is its purpose part of the Q equation? Is it just one of the many factors, like brushstrokes or pixillated flashes or any other condition that occasions the art, but not the key to its quality?

So, what if the purpose of an art is hideous, say targeted at propaganda for ideas I abhor, but the art is good and another art that has noble purposes or is purposeless is instead medioce?

Best, Lucio.

That's a nice reconciliation you arrived at at the end there, Carter: the artist doesn't intentionally make a functional object, but assuming they're not, the product of their creative activity may well result in art with a purpose: "…it has, in its austere way, the social, even ethical purpose of launching an interchange, a conversation, which generates the sorts of meanings that join us to a culture." Well played!