In 1987, the Acquavella Gallery presented works on paper by Robert Rauschenberg. Though he doesn’t get much attention these days, I wanted to post this excerpt from my essay on the exhibition because it focuses on questions of the self, which we also tend to neglect—not that ideas of art as self-expression, self-assertion, self-creation have entirely vanished. Yet Rauschenberg is notable for going beyond all that to address the self itself. Most of what follows is about a series of thirty-four solvent-transfer drawings that turn readymade newspaper and magazine images into illustrations of Dante’s Inferno.

In the Inferno drawing called Canto VI: Circle Three, The Gluttons, reaching hands loom up from a ground at once blurry and scratchy. The hands too are blurred. If we assume that Rauschenberg possesses these images as securely as, say, Fernand Leger possessed his Cubist metropolis or Jasper Johns possesses his version of the American flag, then it follows that Rauschenberg imprints the images of Canto VI with his sensibility. Transferring its found images from their sources to a blank sheet of paper, the drawing produces the furniture of a Rauschenbergian world. If Canto VI does that, it may also send a message: like the hands adrift here, gluttony takes on the quality of the world around it, of all that it would like to ingest; if that world is unfocused, ungraspable, the grasping hand will be the same. That, at any rate, is one way to interpret this drawing if we assume that Rauschenberg makes a vigorous claim to the ownership of its contents. But it’s a dubious assumption because he displays such finesse in encouraging images to slip toward illegibility, even invisibility. Rauschenberg lets go so elegantly, and in so many ways. He’s a virtuoso at it. That virtuosity gives an ingenuous look to allegorical interpretations of Canto VI.

If he lets his imagery slip beyond his grasp, then he can’t really be said to lay the imprint of his sensibility on it. The Rauschenbergian look of his transfer drawings is the product of an irony: he makes his pilfered images his own by refusing to claim them, though he refuses in a manner literally inimitable. (Who else is this good with lighter fluid?) Nonetheless, Rauschenberg lets us know we will never be able to convict him for possession of stolen property. We may itch to bring the charge, we may not be able to resist prosecution, but we cannot win the case. His hands are empty, and the realm defined by Rauschenberg’s drawings occupies no well-defined place on the chart of our imaginations. Blending insidiously into the trash-filled corners of the media-world, it is a nonplace. We come away from a look at these works with the feeling we have been somewhere, yet we are never sure where or even that we ever left the mundane regions of our world’s standard image-overload.

Since Rauschenberg lays only casual claim to his images, he can’t use them as the means to a distinctively Rauschenbergian judgment on gluttony or anything else. His point, if it makes sense to ascribe to him anything so earnest, is that one can hardly be expected to make any points of one’s own with imagery over which one cannot establish any firm ownership—though of course Rauschenberg could have inscribed his found images with deep marks of his personality, like Joseph Cornell or Max Ernst, who took full possession of the images they borrowed.

Forever positing an ethereal ideal, Cornell’s birds and ballerinas look sappy to me: a dream of perfection tinged by the artist’s undying crush on familiar notions of beauty. Rather, they look that way until I accept the idea that Cornell’s ownership of his images somehow rids them of everything banal. To make that decision, I have to let myself be swept away by the fiction of the artist’s absolute and transforming sovereignty over his art. That is, I have to set aside all the questions of possession raised by Rauschenberg’s drawings. In justification of this policy, we can define art’s purpose as the deployment of precisely those fictions of sovereign power. Thus, Cornell is great because he so often gets us to go along with the Cornellian program—because he blunts, instead of sharpening, our critical faculties. Why not? I like the dreamy state that makes the exalted poignancy of Cornell’s art convincing. Or I like it in small doses.

I also like the collages Max Ernst made from nineteenth-century book illustrations. Still, I feel those works are as mundane and predictable in their own way as Ernst’s sources are in theirs, the polemic of Surrealist “revolution” notwithstanding. He is as good as Cornell at getting us to go along with his claim that when he takes possession of an image it becomes something entirely new and better. But I prefer Rauschenberg, who makes only ironic claims to ownership. His transfer drawings admit—even insist—that their imagery belongs and always will belong to mass culture’s image-barrage. By doing without fictions of transcendentalizing proprietorship, Rauschenberg reminds us how important those fictions are to most artists and to us, most of the time.

Collagists, assemblagists, and other image-borrowers bring all this into the clearest focus, but painters and sculptors also try to take possession, not of found images, but of the readymade stylistic options that confront them as beginners. I suppose Gerhard Richter intends his abrupt jumps from style to style to suggest that no style can ever become personal in the way, for instance, one’s body is, though Expressionists make precisely that claim: their styles are aspects of their physical selves. Yet the international repertory of Expressionist mannerisms provides much unintended evidence that any style consists at least in part of shared, impersonal, prefab elements, just like a Cornell box or a Rauschenberg transfer drawing.

Encouraging his images to drift back to the state of banal anonymity where he found them, Rauschenberg forgoes his hopes of constructing a counterpart to Dante’s allegory. That would require the individual standpoint implied by a firmly individual style. Rauschenberg cultivates the irony of a style distinctive for its evocation of the mass media’s power to undermine individuality. So the absence of any comment about gluttony in the Canto VI drawing feels like the comparable vagueness about, say, “the wrathful and the sullen” in Canto VII or “the sowers of discord” in Canto XVIII. In Rauschenberg’s inferno, everyone, sinner or saint, suffers from meaning’s reluctance to come into focus. This torment extends beyond the thirty-four drawings of the Dante series to all the others in this exhibition, to Rauschenberg’s work from this period, and beyond his work, to our media-soaked world, from which Rauschenberg, with such exquisitely tentative care, takes the contents of his art.

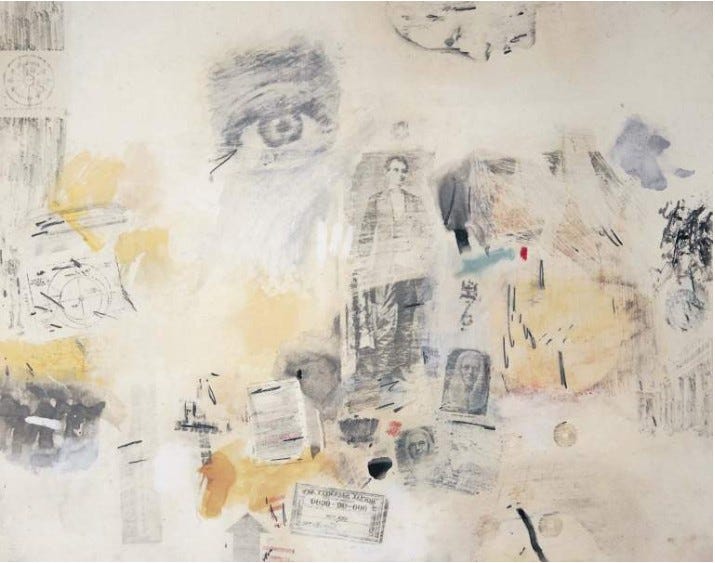

Questions about the firmness of his grip on his imagery become questions about him: what sort of self does his art imply? By collaborating with entropic forces, does he produce emblems of his own sense of disintegration? Such questions gather all of us in. At most, Rauschenberg’s art inflects the world with a recognizable texture. Is it possible for any of us to do more? Fictions of the artist’s and the writer’s absolute sovereignty say that it is, but this is too quick and too positive an answer. Rauschenberg’s tentative touch may not posit the last word, but it gives a powerful shove to an important discussion. Throughout the Acquavella show one saw images of passports, identification cards, bureaucratic forms. Sometimes Rauschenberg inscribed them with his own name. Grayish traces of a Social Security card numbered 0000-000-0000 haunt I Swear, a drawing from 1959. The card’s top line reads “YOUR NAME.” But whose? A world of interchangeable images is the work of institutions for which identities, too, are interchangeable. Rauschenbergian entropy is generous in a way. By drawing only a faint, wavering line between self and other, artist and viewer, it offers the utopian possibility that, as individual as we may seem to ourselves, we are forever merging into an all-inclusive unity.

Rauchenberg like other pre-internet artists was all his own media, one-man program

In the thirty plus years since, it seems that many artists and methods are better "with lighter fluid" . Mass media and mass images have become a culture unto themselves, hushing and percussing high culture of millenia past. Appropriation of images get propelled into garbeldolgook, a Kitsch Culture with a fresh patina. Just stuff. Indeed, few people even know what DANTE is (like a new club ? a type of weed?). Even fewer could say what the genius writer wrote or thought.... after all, it is more than a 'mind-bite', too much for txt.

The explosive 'lighter fluid' event that has transformed our visual, linguistic and knowledge base is the transfiguration from Analog to Digital, accelerating from the time of the 1987 exhibit and your essay to our present 2025. Everything -EVERYTHING- was commandeered into digits, into pixels, into virtual spaces, onto windows, and, most profoundly, new ways to know the world. We can say, to know micro-nuclear, extra terrestrial, human biologies, etc ad infinitum.

We are living inside one of the great human revolutions in knowledge and imaging,which is central to knowledge comprehension and appreciation.

Artists in the analog period saw and rendered from sight to pencil/pen/brush/chisel onto surfaces/stone/clay to bronze. They too used devices like the 'camera obscura' and measuring lay-out systems, such as 'pounching transfers' . The Virtual systematic and pixelating are a different universe, a different dimension ( READ -Paul Virilio ).

This digital/virtual 'lighter fluid' is lighter. It is faster; it is revealing; it sees in filters, vectors , and windows, impossible to the human eye and prompts the human mind thereby. All images and ones never seen before go into the hopper of appropriation and transfiguration.

During the period 2005-2015, my studio used images collected by NASA of extra-terrestrial data sent back from space to depict images of Earth as seen in raw info: 1 or 0 turned into dots dashes, bands, blobs, torques. ( and it was as free as old newspapers to older artists !). The data presented ways of seeing our Earth that had never been seen beofre the NASA probes.

QUESTION- SO WHAT ??

However it may be appropriated, by direct sight and pencil ( yes, I can draw ), or by digital imaging processes, the artistic question will always resonate around about what that Master Artist of the AE period Barnett Newman said; CONTENT.

Every image has some meaning. Propaganda is singular, as in "We the People" say so and you are damned if you don't do so. Interesting artistic work is multi dimensional and even more complex over generations, deepening in interpretations, and expanded by conversations.

This essay presents the critical factor of genuine connection between the maker and the viewers. As you write, Cornell works are fanciful quotes and appropriations but so enchanting that we believe them too. The Rauschenberg CANTOS are elusive in style, due largely to the transfer method itself, because the inks are washed out. .. beautiful. It seems to me that Rauschenberg had a more certain self and more sincere intent in general that a "appropriationist" and in the

CANTOS in particular. He was operating at the beginning of the media flood of imagery so it seems elegant handiwork, and it is elegant.

I suggest that The Gluttony Litho maybe a true representation of one level in DANTE hell, where the gluttons are grasping at one another, slipping down a spiritual tunnel of greed and despair of their own making. The Litho looks like that, slithering sorrow of the gluttons. Neither Medieval

Catholics nor contemporary ones are characterizing a physical realm of bodies but rather a spiritual space and a reality of behaviors. If you look into the spirit of the hedge dudes in Greenwich, Dallas, Frankfurt, or Miami, the litho looks like they feel- lost souls grasping for anything to grip onto and gobble down: Faint, slick and dim.

Like most of the POP Generation, Rauschenberg is critical of the market greed and money run-up that propelled his own and others successes. I suggest this as another meaning of those CANTOS. The Identity Litho prefigures the Surveillance Society mechanisms that have become so repulsive and dangerous some 30 years later--- a potent social critique.

In this regard, alike other social critics of war or social corruption, the artists are communicating with genuine force, being themselves with their own hands, but to critical and caustic ends.

Thanks for another reissue of an earlt essay revealing so much from then to now .