This is an excerpt from an essay on Salvador Dalí I published in Artforum in 1982. Though Dalí is just about the most dubious character in the history of 20th-century art, I feel I ought to acknowledge that he made a serious contribution to Surrealism in the early 1930s. Even Alfred Barr admired him then.

Salvador Dalí’s cane, his moustaches (perpetually at “Present arms”), his Wagnerian strut—the artist flaunts these emblems of masculine creativity with an air both sordid and quixotic. Once given to wearing drag, he now impersonates the grand Nietzschean procreator. To be male, he hints, is only to play at mastery. Dalí lives in fear of impotence, of humiliation, of sinking into that passive state he defines as feminine. He is also afraid that female passivity will turn aggressive: fanged and all-engulfing. Dalí preserves these sexual stereotypes for the sake of rearranging them.

Reconstructing himself in the mirror of his wife Gala’s body, Dalí devised a sexuality of engulfment or, in more recent terms, of consumerism. He recognized himself as a licker and swallower, a masticator and ingester. His post-Gala version of maleness is determinedly “female”—and endlessly versatile. Inspired by her, Dalí turned the androgyny of his transvestite days from a panicky subterfuge into an esthetic of the mouth, an innovation that has made him one of the century’s two or three most famous artists.

His first act under this new regime was to banish signs of self-destructive obsession from his art. As these disappeared, so did the attention of serious viewers. Dalí counts among modern art’s elite so long as he confesses weakness, a Surrealist answer to Cézanne’s doubt, Baudelaire’s spleen, the sorrows of young Werther. Such afflictions of the self are as ironic as they are sincere. The sufferer presents his wounds as the signs of a superiority to which the rest of humanity is, of course, free to aspire. Inverting certain painful symptomatologies, the artist displays them as claims to transcendent strength. Born of privileged vulnerabilities, that strength brings with it a lofty place in our culture’s hierarchy. Denying all vulnerability, Dalí gorges himself at will, urged on by his aesthetic of the mouth. The moment he threw that aesthetic into gear, those with a serious interest in art cast him into the lower depths and that is precisely where he wishes to be, for it is in the limitless mud flats of consumerism, with no heaven of high art above, that his image-ingestion and regurgitation brings him the largest measure of worldly power.

By the late 1930s, Dalí the window dresser at Bonwit’s had become even more offensive to modern art’s defenders than Dalí the right-wing fop. Perhaps Dalí offended most deeply by garnishing his commercialism with strong hints that seriousness is as often as not a sham, that the artist is not a privileged self but a marketable image. As Dalí’s claims for his genius grew more strident, he showed himself readier and abler by the season to mire himself in the pretentions of haute couture and the commercialism of Hollywood. Shamelessly ambitious, he adjusted his aesthetic of the mouth to the scale of the marketplace, where the images of fashion, advertising, the movies, and, later, television are spewed forth by corporations and gobbled up by mass audiences.

When Dalí was still close to the Surrealists, he proposed the entire group, himself included, as a cannibalistic banquet for a public whose imagination had been starved by the realism of popular entertainment. In 1934, the year of his expulsion from the Surrealist cadre, Time magazine swallowed whole a press handout in which Dalí described how he had posed lambchops on Gala’s shoulders, arranged her before a sunset, and then, observing the slow shifts of meat-shadows, managed to paint canvases “sufficiently lucid and ‘appetizing’ for exhibition in New York.” Later Dalí volunteered himself as the entire meal. “I am the most generous of painters,” he said in 1962, “since I am constantly offering myself to be eaten, and thus I succulently nourish our time”—this apropos of his Soft Self-Portrait with Fried Bacon, 1941. Toward the end of the psychedelic ’60s, he updated his offer: “I have never taken drugs, since I am the drug. I don’t talk about my hallucinations, I evoke them. Take me, I am the drug; take me, I am hallucinogenic!”

Reflecting on his Atmospheric Skull Sodomizing a Grand Piano, 1934, Dali said, “The jaws are the most philosophic instrument that man possesses.” The jaw in this painting—a mandible as phallus—doesn’t look particularly “philosophic” at first glance, yet it is like the rest of the artist’s allusions to the body: for all their aggressive twists and ghastly turns, each of them shows a transcendent bent. In 1945 Dalí recalled seeing “at the age of five, an insect eaten by ants” who left “only the clean and translucent shell. Through the holes of its anatomy, one could see the sky. Each time I wish to approach purity, I see the sky through the flesh.” The chief by-product of ordinary consumption—eating—is sewage. The Dalínian eye eats its way through the world, ingesting it and then excreting the pure and the absolute in imagery that is in its turn effortlessly consumable.

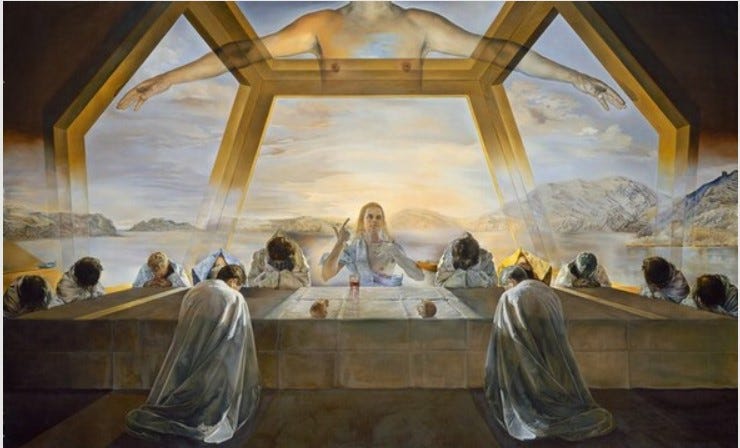

Dalí’s Sacrament of the Last Supper, 1955, is a masterpiece of grandiose banality. He painted it, he says, to corroborate his suspicion that, of all living artists, he is the best-loved—a claim proven, he adds, by postcard sales at the National Gallery. I am not convinced, for love may have nothing to do with it. I am certain, though, that of all the artists anyone ever took seriously, Dalí has produced the emptiest, most easily consumed images. His only rival for this honor is Andy Warhol.

Maybe too jaded, but I feel there are artists of consumerism today.

one weird and unique fellow, Dali. .... It seems the thrill of his taunting has passed.