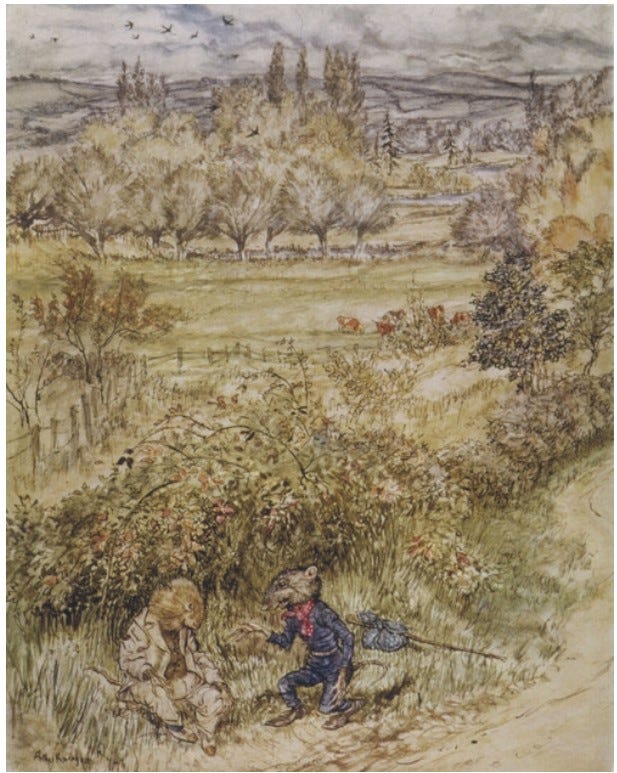

As a kid I loved Hardy Boys books, the Oz stories, Rootabaga Stories, The Wind in the Willows, Stuart Little. As much as the words, I loved the pictures—so much so that I have added a small gallery of illustrations at the end of this post. When I was young, I didn’t ask myself why I so enjoyed my travels through Oz or the cities and Great Plains of Carl Sandburg’s Rootabaga Stories. Now the reason is obvious: these fictional worlds fascinated me endlessly and, more than that, provided refuge from the real world. Adventures in Oz could be scary, but not really, and I always felt safe.

Having swept us away, a fiction eventually lets us go, and we call it serious if we return to the realm of ordinary experience with sharper perceptions, deeper intuitions, a clearer sense of ourselves. By that standard, children’s books are considered childish things to be put away as one moves on to Hamlet and War and Peace. I’m not sure that’s fair, but instead of debating the point I’ll note that Hamlet’s problems both attract and disorient me. Nothing about the play makes me feel safe, and yet I go back to it often, much as I seek out the shadowy, unsettling subtleties of film noir. In painting, I look for the sublime, a quality that originates in terror, as Edmund Burke argued in 1756, and I can’t get enough of the unreassuring complexities of late Cézanne and early Cubism. These are tastes I share with many adults; moreover, I suspect I am not the only one of my age who retreats on occasion to childhood’s all-engrossing fictions. And sometimes they come to me. Imagine how surprised and happy I felt, in 1980, when Robert Altman transposed Popeye from cartoon to live action.

Those indignation-prone people known as film critics nearly all panned the movie, calling it silly, unfunny, boring, cluttered, incoherent. And they were impervious to Robin Williams’s brilliantly irascible turn in the leading role. Popeye made a modest profit and a few critics found reasons to approve. Still, this was not the blockbuster Altman’s backers expected. The director spent the next decade working in theater and television, and his venture into kids’ fiction took decades to become a cult favorite. I was quicker. After just one viewing, I awarded it cult status, right up there with Out of the Past, my favorite film noir. There are innumerable things I like about this movie. For one, Shelley Duval as Olive Oyl is as enchanting as Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep, my third favorite film noir, after Beat the Devil, a send-up of the genre featuring Gina Lollobrigida as an Anglophile in love with the civilized pleasures of the Staffordshire countryside.

Though Altman’s Popeye can stand up to as much attention as we are able to give it, I am going to focus on one of the songs Harry Nilsson wrote for the movie’s soundtrack: an anthem named “Sweethaven,” after the village where the story takes place. A three-dimensional variation on the settings in Thimble Theater, the Popeye comic strip that preceded the Popeye cartoons, Sweethaven is all weathered siding, rickety staircases, and out-of-whack rooflines. Nilsson’s song begins with gratitude for divine Providence and moves on to an echo of the United States Constitution.

Sweet, Sweethaven

God must love us

We the people

Love Sweethaven

Hurray, hurray, Sweethaven

Flags are wavin’

Next we hear

Swept people from the sea

Safe from democracy

Sweeter than a melon tree

Put here for you and me

Sweethaven

Sweet, Sweethaven

I don’t quite get “Swept people from the sea” and “Safe from democracy” also puzzled me until I figured out that it is the citizenry’s grateful comment on the nature of their collective being. For they are not autonomous individuals. They are products of their author’s imagination: subjects of an autocracy.

You might want to say: what author? Movies are collaborations between many people; that’s why it takes so long for the credits to roll. True, but Altman was completely in charge of Popeye; everything in it must be blamed on or credited to him. Here’s an analogy from another line of work: naval warfare. Though he supported the democratic ideals of the American Revolution, the heroic Captain John Paul Jones said, in 1775, “True as may be the political principles for which we are now contending … the ships themselves must be ruled under a system of absolute despotism.” Democracy has no place on a warship or in the process of creating a work of the imagination. Actors who rebel against a director’s demands tend to get fired. And no one with a speck of sense would tell a painter how to paint a painting.

When I first showed up in the art world, the air was filled with rumors that certain color-field painters took advice from Clement Greenberg on how to improve their canvases. Those stories, I suspect, were signs of the resentment Greenberg inspired. But what about Andy Warhol, who was notorious for asking friends to supply him with themes? Always open to suggestions, he nonetheless remained the arbiter: he would accept a proposal only if he liked it. As a commercial artist, he had been much appreciated for his willingness to make all the revisions an art director might require. As a fine artist, he was as despotic as John Paul Jones. So is any serious painter.

And now for a sudden swerve: the moment a work of the imagination faces its audience, autocracy gives way to democracy. Absolute, one-person control over the work ends as it becomes an equal-opportunity object of interpretation. Because we all have the right to respond as we see fit. This right is not, in practice, always respected. There have long been critics, historians, theorists, curators, and even collectors who try to usurp the artist’s autocratic prerogative and dictate our responses. They want to save us from democracy. These arrogant ones are among the art world’s bad citizens—and I use the word “citizen” deliberately, for citizenship is the issue.

In the art world as in the nation, we have a civic responsibility to be whoever we may be, shaped by our best values and ready to advance those values not only in private but also in public. For we are not like the inhabitants of Sweeethaven, characters in a story shaped by an author with absolute power. We are free, though not absolutely. Each of us is constrained in any number of ways. Yet everyone possesses some measure of freedom and that common possession sustains our hope of democracy.

Sweethaven by Harry Nilsson

Sweet, Sweethaven

God must love us

We the people

Love Sweethaven

Hurray, hurray, Sweethaven

Flags are wavin’

Swept people from the sea

Safe from democracy

Sweeter than a melon tree

Put here for you and me

Sweethaven

Sweet, Sweethaven

God must love us

We the people

Of Sweethaven

God must have landed here

Why else would he strand us here

Where the air is nice and clear

Sweethaven even sounds so near

To Heaven

God will always bless Sweethaven

God will always bless Sweethaven

God will always bless Sweethaven

I can’t give you a direct link to the Sweethaven video, but you can get to it by double-clicking on “Watch on YouTube.”

In the artistic community, we all need to cherish our freedom and protect it, indeed.

May I add a thought: The Dadaists ands Surrealists pursued a special directive. They sought to create works open to interpretation, so the viewers had the freedom to see, while these creators allowed themselves to draw out, compose and arrange variations. Umberto Eco has presented this theoretically as "The Open Text". It seems possible to dictate openness so audiences can enjoy more freedom in response. I feel a perplexed fascination and inner awakening when I see , hear, read such works.

Thanks to all those emphatic freewheelers !

To my fellow Wind in the Willows fan.....thank you for this is terrific piece! I especially love the bit about Warhol, "As a commercial artist, he had been much appreciated for his willingness to make all the revisions an art director might require. As a fine artist, he was as despotic as John Paul Jones. So is any serious painter. " Having been in the commercial world, while always maintaining my own art practice, I can relate to this as I'm sure many other artists can. Making one's own art is an all out, no excuses, direct experience of expression without a care about anyone's future critique....or so it is for me. Art making: a zone as free the imagination can manifest...ahhhhh, relief!