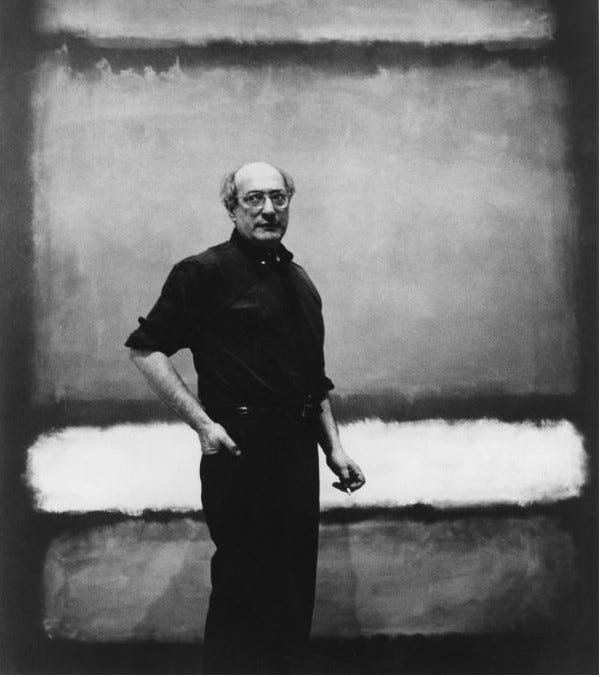

This is an excerpt from one of my essays on Mark Rothko. Here, as always, I end up by talking about the faith his art invites—or demands. It is a demand that all art makes, though often not as openly as Rothko’s does. I’ve come to feel that his openness in this matter is exemplary,

In 1940, a small band of avant-garde artists in Manhattan formed a group called the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Their goal was “to promote the welfare of free progressive artists working in America.” As German forces invaded Belgium and the Netherlands, then France, some Federation members advocated a direct response to the military and political crisis in Europe. By 1942, however, the group had united behind the belief that artists have a responsibility to realize their individual destinies. Rather than address the moment’s crises—as American social realists of the 1930s had done—members of the Federation would perform their “social obligation to keep and protect freedom.” Thus, the group statement continued, these painters and sculptors would “stand for the kind of artistic independence the world struggle symbolized.” In a time of darkness, creative individuals would preserve the light of liberty.

In the Federation’s third annual exhibition, which opened in the summer of 1943, a painter named Marcus Rothko, then 40 years old, exhibited a painting entitled The Syrian Bull,1943. Quasi-figurative, it shows a yellow, eight-legged form against a cloudy, bluish-gray sky. Looming above this shape are angular patches of red, brown, and blue. Feathery white textures mediate between these colors and the extravagantly organic form in yellow. Rothko let it be known that The Syrian Bull invokes the legend of Mithra, the Zoroastrian god who created the world by slaying a bull. Ancient Persian bas-reliefs depict this event in stylized detail. In Rothko’s painting, bull and god emerge only partially from an image generated by means of automatic drawing—a method Rothko, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, and other New York artists learned from the Surrealists, many of whom were in exile in America during the war years. With the help of Rothko’s clue, it is possible to glimpse the subject of his painting. But Edward Alden Jewell, an art critic for The New York Times, confessed his bafflement. Advising his readers that “you will have to make of Marcus Rothko’s ‘The Syrian Bull’ what you can,” he didn’t hazard any guesses of his own.

Jewell had given Adolph Gottlieb’s The Rape of Persephone,1943, the same dismissive treatment. Within days, Gottlieb and Rothko wrote Jewell a letter declaring that their images were not puzzles to be deciphered. For “the point at issue, it seems to us, is not an ‘explanation’ of the paintings but whether the intrinsic ideas carried within the frames of these pictures have significance.” In concert with Newman, who contributed to this letter but claimed no credit for it, Rothko and Gottlieb insisted that their works have their ideas intrinsically, not by way of reference or evocation. What does this mean? These artists were never able to say.

Rothko committed suicide in 1972. Two years later, Harold Rosenberg assigned him to “the theological sector of Abstract Expressionism,” along with Gottlieb, Newman, Clyfford Still, and Ad Reinhardt. Believing that progress requires deletion, each of them sought to pare the image down to what Rosenberg called “an ultimate sign” that conveys “an ultimate meaning.” The 1943 letter to Jewell describes that meaning as “tragic and timeless.” As Rosenberg later noted, viewers resistant to meaning of that sort will judge the art of Rothko and the others according to taste—a standard they considered superficial and corrupted by a marketplace that defines art as a pleasing amenity. What Rosenberg leaves unsaid is that, for a “reductive theologian of painting,” an audience worthy of the name must be capable of faith. To experience Rothko’s art in a manner consonant with his aspirations, we must believe wholeheartedly in its power to reveal meanings that transcend the power of language. Before the ineffable, we willingly fall silent.

Peggy Guggenheim, a collector, and founder of a Manhattan gallery called Art of This Century, gave Rothko a solo show in 1945. Two years later, Guggenheim closed her gallery, bequeathing her roster to Betty Parsons. By then, Rothko’s delicately linear suggestions of biological form had vanished, replaced by patches and streaks of high-keyed orange, yellow, and green. Simplifying these flat, chromatic patterns, Rothko arrived, late in 1949, at the stacked blocks of color that typify his signature style. During the last two decades of his career, the only significant development in his art was a further reduction of his severely reduced format.

Ten Rothko canvases were shown in the United States Pavilion at Venice Biennale of 1958—a sign that the art-world establishment saw in him a painter of the utmost seriousness. During this period, he accepted a commission to provide a series of paintings for the walls of the Four Seasons restaurant, in the Seagram Building, a skyscraper on East 52nd Street. If Rothko had completed the project, it would have reinforced the doubts of those who wondered if his elegantly abstract canvases were simply luxurious décor. The artist, too, felt these doubts. In 1959 he returned the money advanced for the Four Seasons project.

New York’s Guggenheim Museum exhibited “Five Mural Panels Executed for Harvard University by Mark Rothko” in 1963. The next year, Dominique and John de Menil commissioned him to paint a series of panels for the chapel at the University of St. Thomas, in Houston. The year after that, he received the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award. And Marlborough Gallery, a major new presence at the heart of the Manhattan art world, invited him to join its roster. Yet Rothko was increasingly uneasy about showing his work. Moreover, his health was declining.

Hypertension led to an aortic aneurysm in the spring of 1968. Long a heavy drinker, he was found to be suffering from cirrhosis of the liver. Rothko’s relationship with Mell, his second wife, grew ever more difficult. With his perennial depression deepening, he received a diagnosis of emphysema. Having left Mell and moved into his West 69th Street studio, he launched a series of dark gray, black, and brown paintings. By the end of 1969, he restricted his paintings to blocks of black over scumbled fields of gray. Early the following year, rather than keep an appointment to select works for an upcoming show at Marlborough, Rothko killed himself.

Decades earlier, in 1949, he had written, “The progression of a painter’s work, as it travels in time from point to point, will be toward clarity: toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea.” Among those obstacles are “memory, history or geometry”—anything that mires the spirit in “swamps of generalization.” Purity and thus Truth are in the specificity of an image entirely unencumbered and therefore clear. “To achieve that clarity is, inevitably, to be understood.” Or so Rothko desperately needed to believe—and in the end could not believe with life-sustaining certitude.

As always, Carter was prophetic. " (..) power to reveal meanings that transcend the power of language. Before the ineffable, we willingly fall silent. (...)

The ineffable is still the force, maybe the only one, we can seek to avoid dependence on packaging explanations, because value is in the intrinsic power of each single piece, not in the context it can however never do without.

But even Rothko fell for the tradition of Modernist defensiveness when he tried to set the boundaries of creativity. Memory, history, geometry are as legitimate instruments to achieve quality as any other, including the reduction to essential forms.

thanks for reviving this essay; his death seems sadder in retrospect. I have always wondered why the Artist doubted himself so much and his communication, because so so many people have been transfixed and transformed before his works. What a great achievement.