One afternoon in the 1970s, I was sitting around in the Spring Street Bar with a few writers and artists. One of them, the art historian and critic Robert Pincus-Witten, suddenly but quietly said, “I have no use for the experiential sop.” As he used the word, a sop is anything that distracts or conciliates but has no great value. The implication of his remark was that some attend closely to their experience of art, some even feel that the value of art is in their experience of it, but they are wrong to do so. The experience of art is beside the point. No one had raised the issue of art and experience—that wasn’t the sort of thing people talked about at the Spring Street Bar—so I don’t know why Pincus-Witten made his declaration just then.

He was an editor at Artforum, where I had recently begun to publish. I didn’t work with him on any of my pieces, but he may have read them and realized that when I write about art I don’t make judgments about quality, I don’t rank artists, I don’t sift through images in search of detachable messages. I try to convey my experience of the work in question, an effort that leads me to a sense of the work’s meaning. How, you might ask, does that work? I’m not sure, though the transition from experience to meaning originates, I think, in our emotional and even physical responses to form and color—and subject matter, if there is any. Take, for example, Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm, 1950.

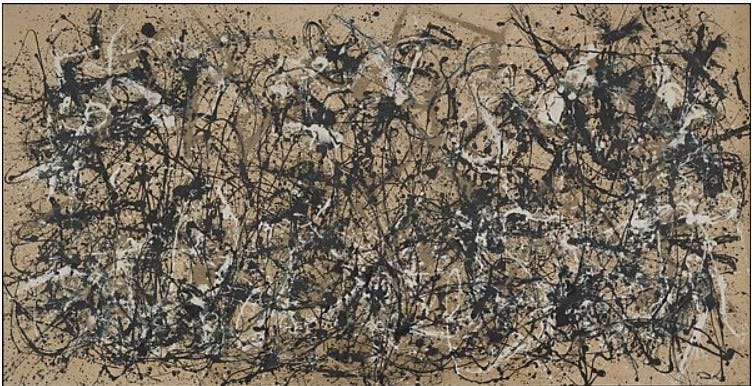

At risk of sounding too rhapsodic, I’ll say that the currents and crosscurrents of Autumn Rhythm stir in me a tangle of feelings that range from exaltation to apprehension. And these feelings never resolve themselves, never come to rest—as, for a counterexample, my response to a painting by Piet Mondrian always does. Integrating subtleties of placement with overarching structure, guides each of his compositions to a grand equilibrium. Every painting feels serene and from its serenity flows its meaning: its proposal that order can be all-embracing without being oppressive, that clarity and calm can be, not dull and predictable, but exhilarating. Elaborations of these meanings fill Mondrian’s utopian writings. Pollock proposed no utopia and Autumn Rhythm is endlessly agitated. Its most salient drips and spatters intertwine and yet they have a strange independence, hence its incidents of order are all local. A unifying composition never emerges, meaning—and I want to stress the word meaning—that the painting is not just a stunning, enveloping array of contingencies. It celebrates contingency and the view that life is both dangerous and wonderfully unfettered. Because my experience of Autum Rhythm is subjective, the meanings I derive from that experience lack even the faintest tinge of objectivity. Art historians find this unacceptable.

The website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns Autumn Rhythm, notes that it is a large, mural-like painting, and that Pollock said he wanted his “pictures” to “function between the easel painting and the mural.” Moreover, he worked with the Mexican muralist David Siqueiros in the 1930s. These are objective facts. It is also a fact that Pollock was acquainted with the Surrealist theory and practice of automatic drawing, which has an evident affinity with his drip-and-pour method. Art historical facts like these are always interesting and sometimes illuminate experience, by refining our sense of the connections between artworks, artists, and art movements. Facts are good, but it is not good when an art historian presents an account of a career or an era as a finding comparable to that of a laboratory scientist.

I realize that most art historians make no explicit claim to scientific objectivity. Yet they do claim that their methods of research and analysis exclude subjective responses to works of art. For art history is an academic discipline defined by the impersonal standards it imposes on its practitioners. To be an art historian is to be professionally respectable and not the sort of writer who indulges individual tastes. For art history presents truths, not evocations of unverifiable and hopelessly personal experience. Two things need to be said. First, art historical objectivity is a delusion with no power to hide the predilections and biases that shape its conclusions. Second, a few art historians are alive to their experience and manage to integrate it with their findings in an illuminating way. See, for example, Linda Nochlin on the realist tradition that began with Gustave Courbet. Striving for unsullied objectivity, nearly every other art historian drains art of meaning.

This judgment may seem harsh, but remember: the meaning of art originates in the experience of art. If your standards of professional propriety require you to ignore that experience, you will say nothing about meaning—nothing about you reason for looking at art in the first place, and, having looked, caring about it. An art historian might say, hold on, I care enough about avant-garde painting to have given a brilliant account of the way Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso derived Cubism from the late paintings of Paul Cézanne. Fine, it’s brilliant, but you have talked exclusively about the how and overlooked the why. Only when we ask why Cézanne made this cluster of marks or Braque stuck that piece of newsprint to his canvas do we begin to feel our way into the image and to empathize with the energies, the intentions, the aspirations that brought it to completion. Why questions lead to speculations about purpose. About meaning. These speculations are always questionable and endlessly revisable—my idea of why Pollock made this or that mark changes even as I look at Autumn Rhythm—and that is why art historians faithful to the standards of their profession resist the temptation to speculate. As they see it, the point of art is neither in the experience of it nor in its meaning. Its point is to provide an occasion for the exercise of their academic skill.

As I have said, art history draws patterns of influence that focus my attention, even if they leave me unconvinced. Likewise, its analyses of themes and motifs can be helpful; so can its attempts to place works of art in their cultural settings. I am not against art history. I am against the idea that our understanding of art should stop short with its findings. Persuasive or dubious, these findings are no more than starting points for the experience of art. And there are other starting points in feeling, in memory, in the speculative imagination. Though art historians dismiss “the experiential sop,” they are willing to coexist with critics who revel in it. The proponents of art theory are less accommodating. For they are rejectionists who deny the value of everything but the dogma they impose on works of art. This dogma not only destroys meaning; its amateurish intellectualizing brings a dreary shallowness to art-world conversations. Nothing in the art world is more destructive than art theory except for writing that focuses on the art market and thereby has an even more ruinous effect on meaning.

I agree with what you say here. My teacher was a student of Hans Hoffman who was very clear about the distinctions between the art historical tradition, art criticism and what he called the “studio tradition”. The last was handed down from teacher to student while actually working. They emphasized that that tradition was recorded nowhere except in small hastily drawn diagrams on scraps of paper or by the teacher actually doing work on the students’ drawings and which gradually erased through the process of continuing the drawing.

Carter, I enjoy reading your articles very much, and was wondering if you have already or would consider devoting an article to the role of the title in a work of Art, and its power to either add to or detract from the overall presentation. I believe a successful title will often blur the line between Art and Poetry, while a poorer title will render the artwork little more than a serviceable illustration.