This is a revised excerpt from “Barney’s Light,” an essay on Barnett Newman that I published in 2002.

Last March, the Philadelphia Museum of Art presented the first full-scale Barnett Newman retrospective to be seen since 1971. Later this month, it will open at the Tate Modern, in London, for a three-month run. Organized by Ann Temkin, a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum, this was an impressive show, though it didn’t have the narrative thrust one might suppose is built into the very idea of a retrospective. Once past the first gallery, with its selection of Newman’s early, biomorphic pictures, I never sensed the sweep of a story-arc, as screenwriters say when they invoke the ideal of an Aristotelian plot with a unified beginning, middle, and end. This is not a complaint. Newman ushers us into a perennial now, and Temkin’s show looked as fresh, I imagined, as the artist’s first solo exhibition, which took place at the Betty Parsons Gallery, in New York, in 1950.

Newman made large claims for the primacy of the solitary creator. “The aesthetic act always precedes the social one,” he wrote in 1948. Yet Newman was far from asocial. During the Depression, he ran for mayor of New York on a quixotic, art-for-all ticket, and he always insisted that he was no alienated, ivory-tower abstractionist. He believed that, properly understood, his art would be socially beneficial—would, if comprehensively seen, “mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.” Yet all the available definitions of the collective left him cold. Art, according to Newman, can have a beneficial effect only on individuals, one by one, as it brings them alive to their individuality.

A corollary of this conviction was his impatience with talk of space, which he called “a communal fact.” Time is more important, for it

is personal, a private experience. . . . Each person must feel it for himself. Space is the given fact of art but irrelevant to any feeling except insofar as it involves the outside world. Is that why critics insist on space, as if all modern art were an exercise and ritual of it? . . . The concern with space bores me. I insist on my experiences of sensation in time—not the sense of time but the physical sensation of time.

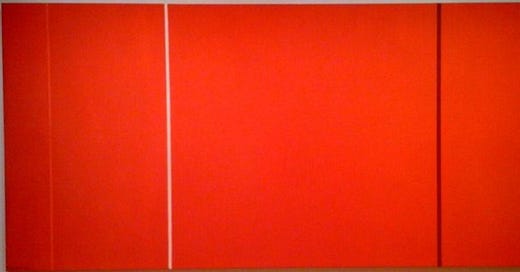

To have this sensation, we must break a deeply ingrained habit. Rather than stand back for a full view of a twenty-foot canvas—Anna’s Light or Vir Heroicus Sublimis—we must come close, so close that the field of color reaches past the limits of vision. Then, the interest in pictorial space gives way to an immersion in a moment colored, literally and metaphorically, by shifting immediacies. Rather than stand in one spot, we are to range back and forth and feel the rhythms introduced by the artist’s vertical stripes—his “zips,” as he called them.

Never predictable, these rhythms charge the field with a feeling of contingency. And even when we move back for a wider view, Newman’s asymmetries still refuse to settle into stable compositions. We might expect stability from the symmetrical images that began to appear in the 1960s—see, for example, 18 Cantos and Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue II, 1967—yet Newman foils that expectation with monumental subtleties of proportion and scale. Or so it looks to me, for there never comes a moment when I feel that I have seen a Newman image once and for all. Rather than click into place with all the precision of a composition by Mondrian or, for that matter, Tiepolo, Newman’s forms keep calling their internal relationships into question, moment by moment, and thus my immersion in a field of color immerses me in the flow of real time. At its most intense, this awareness of time and contingency ushers in a state of exaltation focused, ultimately, on me. Thus I find my way to the subject of Newman’s art, which he described as “the self, terrible and constant.” Fleeing the terribilitá of one’s isolated self, one returns to the reassuring but less consequential realm of shared experience.

Temkin’s installation gave every painting, even the biggest, the two things it needed: enough space for it to be seen in self-sufficient isolation and enough proximity to other works to let us see connections. Beautifully paced, the show leads one to see that Newman’s entire oeuvre—or all the work that succeeded Onement I, 1948, the first painting with a zip—is a play of theme and variations. I don’t mean to deny the diversity of Newman’s art, which is astonishing. As the field changes size, shape, and color, the zips create new tempos. Zips and fields alike show wide—and often overlooked—variations in facture. Temkin’s notes on the complexities of Newman’s studio techniques make it impossible to go on seeing the zips as the products, merely, of masking tape and humdrum brushwork. To keep these elements of the image alive, Newman made himself into a virtuoso of sorts, alternating deliberate feathering and scumbling with less easily controlled effects of bleeding and soaking. In his way, he was a painterly painter, which is not to say that the “Abstract Expressionist” label can be made to fit his work.

Obviously not representational, Newman’s paintings are not expressive, either. They are declarative, and with every canvas he tried to tell us everything he thought art should say about the endlessly shifting fears and exaltations of the human condition. Among the last works in the Philadelphia show is Jericho, 1968-69, which Newman completed by splitting its black, triangular field with a stripe of red. Displaced just a bit from the vertical axis of the triangle, this stripe drastically destabilizes an inherently stable shape. With a single gesture, he breaks a closed form wide open. Cued by the title of the painting and Newman’s writings, you could see the openness of Jericho as a triumphant declaration of freedom. Bringing down the walls of Jericho with just one trumpet blast, Joshua won the battle that opened the way to the promised land.

Newman’s promised land was America, though he was frank in acknowledging that many of its promises had not been kept. Nonetheless, he accepted the American idea—Jacksonian or Emersonian, as you wish—that freedom is not for nations or peoples, not for social classes or interest groups, but for individuals conceived apart from those larger entities. Though freedom was crucial to everything he valued, Newman understood that it often leads the individual into isolation and worse. That, in part, is why he saw terror in selfhood. Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is joyous. For Newman, that song is tragic. His friend Rothko, too, talked of tragedy, and his later work is melancholy, if not Aeschylean. Oddly, Newman’s art shares little of Rothko’s gloom. Jericho is foreboding, even solemn, as are Achilles and Prometheus Bound, both 1952. A note of solemnity recurs at irregular intervals throughout his career. Still, the prevailing weather of Newman’s art is as bracing and sunny as that of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass or of Emerson’s happier essays. For Newman, I think, the greatest terror was indistinguishable from the exhilaration that accompanies a sudden sense of the inescapable contingency, the exalted fragility, of one’s being on earth.

Great analysis of the profundities of Newman and his larger project. His idealism is at once inspirational and heartbreaking.

This is a wonderful reminder of the spirit of "first generation" NY Artists. Significant meanings or Meta-Physical concerns lay behind and within their works... "the greatest terror was indistinguishable from the exhilaration that accompanies a sudden sense of the inescapable contingency, the exalted fragility, of one’s being on earth" captures the feeling before Newman's works- Solemn, poignant, and significant- alive like Whitman, never morose or resigned to another fate but the individual.