Distancing us from things, art brings us closer to them. Is this a paradox? Or just a contradiction? Whatever it may be, it gets at something I would like to elucidate. I’ll start by mentioning Edward Bullough, a name that is big only among those philosophers who specialize in aesthetics. In 1912, he published a paper called “‘Psychical Distance’ as a Factor in Art and as an Aesthetic Principle.” The distance he had in mind fosters a detachment that puts a “phenomenon … out of gear with our practical, actual self … allowing it to stand outside the context of our personal needs and ends.” The phenomenon may be natural—his example is a fog at sea—or it may be a work of art. In any case, the moment we establish aesthetic distance we no longer view the phenomenon as an impediment to navigation, as a source of information, or as a bearer of monetary value. Aesthetic distance places it beyond any consideration of usefulness or threat. Bullough’s account of fog viewed first as a danger then as an aesthetic object is brilliant but not entirely original, for it reworks disinterestedness, an idea basic to modern notions of art.

For most of history, art images and objects had practical uses. A statue of Athena provided her cult with a palpable focus. A painting of Christ, like the interior of a Gothic cathedral, its vast gloom pierced only by sunlight sailing through a stained-glass window, encouraged religious veneration. Portraits of kings asserted claims to authority and renderings of mythological subjects taught moral lessons. Qualities we now call aesthetic were meant to reinforce the lesson, the claim, the power of the statue, the painting, the building. Then, early in the eighteenth century, something new appeared: the possibility of appreciating those qualities in and for themselves, apart from any social or political or religious interest.

We call harmony and balance and dissonance aesthetic qualities because, in 1750, a German philosopher named Alexander Baumgarten reframed the word to gather them under this general heading. Thanks to him, we call the entrancing flicker of light in an Impressionist painting aesthetic. We do not, however, apply the word to all the painting tells us about French society in the 1880s. For our interest in social history is practical, unlike the experience of pictorial luminosity, which is self-sufficient and autonomous—and thus disconnected from the interests of ordinary life. That disconnection is the premise of the disinterestedness that Baumgarten’s argument implies. Immanuel Kant took up the subject next and followed it to the startling conclusion that, when we have attained a truly aesthetic view of a painting, we do not feel an interest, even, in the object’s existence.

Baumgarten and Kant found the idea of disinterestedness readymade but lacking philosophical rigor in the writings of Lord Shaftesbury, Archibald Alison, and other British writers; after the Germans came Victor Cousin, Théophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, and a phalanx of nineteenth-century French aesthetes who elaborated the idea into various doctrines of art-for-art’s sake. In their wake emerged the English advocates of pure, disengaged art—Walter Pater, Roger Fry, Clive Bell, Edward Bullough—and their American followers, chiefly Clement Greenberg. So there you have it, more than three centuries of argumentation designed to convince us that the experience of art as art (to borrow Ad Reinhardt’s phrase) is apart from and superior to any other sort of experience. I disagree and yet I do not deny that a disinterested view of a painting or a sculpture has the virtue of focusing our attention.

Undistracted by morality or your political leanings, by curiosity about the artist’s life or the market value of an artwork, you find that its details become vivid; as you look, the relations between details and the work’s larger forms map themselves with a lovely insistence. Everything from subtleties texture to the flow of color (if you are looking at a painting) acquires a significance that seems to have nothing to do with anything but itself—and this feels strange if the painting under scrutiny is representational. It’s not that you look past the subject; rather, you don’t care about it in any familiar manner. Nothing counts but the pictorial qualities of the picture. Hyper-alertness is usually driven by anxiety. Here it is indistinguishable from a passionate serenity that can turn perceptions into lasting memories.

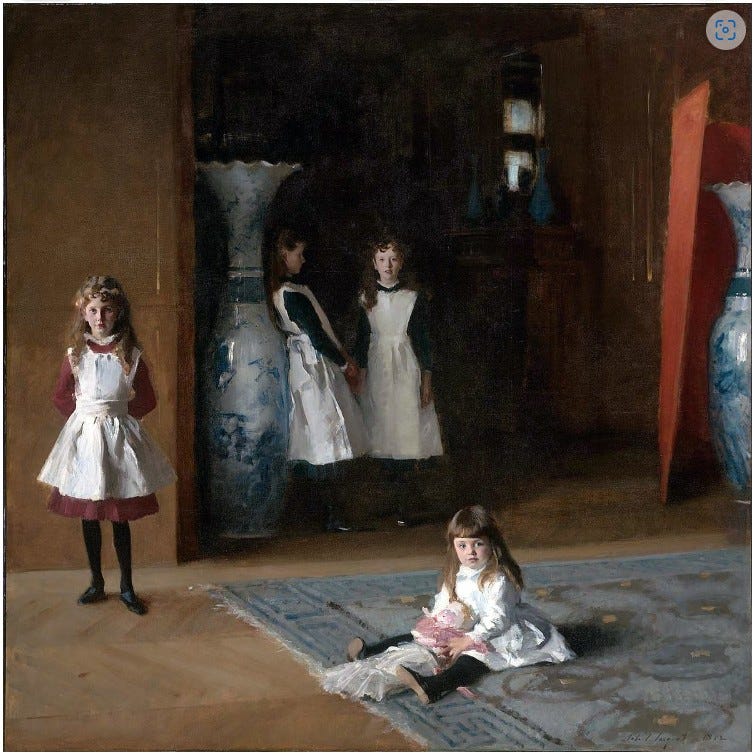

When I was writing about John Singer Sargent, I looked for a long time at his portrait of the Boit daughters, and I still remember with precision the nonchalant elegance of a certain brushstroke in the foreground of the canvas. My memory of the pigment dripped over the collage element in one of Jackson Pollock’s small paintings is as bright and exact as my memory of the constellation known as the Big Dipper. We generate memories like these with a gaze different from the ones we direct at those we love, at political situations, at economic opportunities, or at anything in which we have an interest. When we look at a painting as a painting and nothing but a painting, our only interest is in our looking. That is where the ideas of disinterestedness, art-for-art’s sake, and pure art take us—and that is where they leave us, alone with a work of art. End of story, until we turn away from art and reenter the world of practicalities. This is not a satisfactory ending.

I said at the outset that, by distancing us from things, art brings us closer to them. To make sense of this I should note that the kind of attentiveness inspired by aesthetic distance can carry over from the experience of art to the experience of everything else. When this happens, it gives us a full and fully nuanced view of the world and thereby prevents our interests from functioning like blinkers. When this happens, we are more present in our surroundings, more responsive to the others who inhabit those surroundings with us. It makes us more humane. Only art in all its modes and mediums can have this effect on us, for only art has the power to extract us from practical life and return us to it with all our faculties enhanced.

Appreciate the thoughts of a man who cares about his subject more than himself.

Regardless I have some disagreements and comments. (It’s to be expected here.)

“Distancing us from things, art brings us closer to them. Is this a paradox? Or just a contradiction? “

While I realize this opening is for a rhetorical effect, I’ll still comment in earnest, that the perceived contradiction is remedied by an ontological and phenomenological approach, to echo nicholai Hartmann, the aesthetic stratum of phenomena is, experientially an addition to being created by all of the already-existent elements of being that we encounter, abstracted and modified by the fact of being no longer ready-to-hand, but, by being present -at-hand, that is, by the conscious perception of the datum as a thematic center, is the object modified by both the first apparent elements of its constitution, which are then modified by the build up of the eidetic categories to which its constituent elements are composed, thus the aesthetic experience is an approach into unity with the idea of the aesthetic piece, centered on your own narrative of experience of the many objects and art pieces, that is, the Virtue is in the Vertue collectively approached.

“ he published a paper called “‘Psychical Distance’ as a Factor in Art and as an Aesthetic Principle.” The distance he had in mind fosters a detachment that puts a “phenomenon … out of gear with our practical, actual self … allowing it to stand outside the context of our personal needs and ends.” The phenomenon may be natural—his example is a fog at sea—or it may be a work of art. In any case, the moment we establish aesthetic distance we no longer view the phenomenon as an impediment to navigation, as a source of information, or as a bearer of monetary value. Aesthetic distance places it beyond any consideration of usefulness or threat. “

This affirms my prior statement, though I think something needs to be added, deleuze’s conception of the baroque-Fold, I think, is intrinsic to any art piece, that is, the art piece having the interior layer of self conscious as art piece among art pieces immediately modifies how a given gentleman may construct it, no art piece is free of rhetorical propaganda nor of being a historically placed microcosmology of ideals and various schools, this does in fact divide the aesthetic object from the simplistic aesthetic appreciation after a manner, until one realizes that we carry our aesthetic treatment of our art into the world itself. How Wordsworth must have viewed a tree vs Walter pater, despite the direct lineage in style among them, must be a monstrous difference, owing to the art they’ve consumed modifying and uplifting the category of the object in itself.

I think we all have experienced this in practical terms, for example reading a very very pleasurable description of a bath or shower, and, upon showering again, finding our own pleasure is somehow magnified by a layer of conscious that was somehow non existent prior.

“For most of history, art images and objects had practical uses. A statue of Athena provided her cult with a palpable focus.”

This is an over-exaggerated utilitarianism you’re placing in history, Philostratus of Lemnos' Eikones is an example of Ekphrasis but also packed with historical examples of pure aesthetic appreciation and conception of the arts held by the ancients, we also see pure erotic and sexual and aesthetic treatments recorded, I think of Pliny’s treatment of the Aphrodite of Cnidus, describing how people around the world would journey to see the statue, and “ferunt amore captum quendam, cum delituisset noctu, simulacro cohaesisse, eiusque cupiditatis esse indicem maculam” (They say that a certain someone, seized by love, when he had hidden himself in the night, he pressed his body on the statue and the proof of his lust is a stain (on the statue) (Naturalis Historia, 36:4) we may also add to this numerous aesthetical essays, ranging from Aristotle downwards.

> Qualities we now call aesthetic were meant to reinforce the lesson, the claim, the power of the statue, the painting, the building. Then, early in the eighteenth century, something new appeared: the possibility of appreciating those qualities in and for themselves, apart from any social or political or religious interest.

I think that, this idea that the aesthetic is somehow separate from the cloud of ideals pervading it, is wrong headed. Schiller in his letters on aesthetics speaks at length of the play-drive, that, the primary drive behind the aesthetic works is a sort of, redundant, non-necessary, but, paradoxically, pure appreciation in ideal, the good-for itself, enjoyable-for itself. Far be it from the vulgar interpretation of art-for-itself, but like the world-enamel’d name of Gautier, understands that the value of the aesthetic is the essential element of what aesthetics are, the free-enjoyment of the highest ideals having utterly dominated the base materia and elements of sensation, performed by the illusion of the annihilating of the foreground of object-apprehension (in painting, the canvas and individual paints and individual subjects, in music the individual instruments, in writing the vocal glyph and simple referents ) and the conjuring of the foreground, arising like a field of stars from the dark abyss of the object.

“when we have attained a truly aesthetic view of a painting, we do not feel an interest, even, in the object’s existence.”

While this is true, Kant and Hume, like Henri Bergson, hold that even in the dispassionate de-personalized and even transcendental(non empirical world) there is something of delicacy of taste and art necessarily still generates a suspension of the rest of the world into a kind of absorbed-wonder, this suspension is the basis of the aesthetical treatment of Schopenhauer, which when laced with the evolutionary perspective of Wagner accounts for the intellectual basis of the symbolist, decadent and latter Parnassian artists.

“We generate memories like these with a gaze different from the ones we direct at those we love, at political situations, at economic opportunities, or at anything in which we have an interest.

I think that, this is the bias of the art critic, and not true in reality, for, wherever the particular can generate an experience of the great-universals (whether the sublime through the profane as the modernists or simply the experience of the great and mighty ) there do we find these aesthetical experiences and memories, so that, the political radical finds the spiritual completion and absorption into the passions of eternity via his political actions (regardless of our personal opinions, surely Otoya Yamaguchi experienced this in his moment.) likewise the “hustler” aestheticizes his hustling, a film like uncut gems was a successful worship of the lifestyle because, to a category of people, this is a form of the higher-Life. (An image of Rajas) and surely endless ink has been poured trying to capture and enhance the romantic and filial moments of life.

“Only art in all its modes and mediums can have this effect on us, for only art has the power to extract us from practical life and return us to it with all our faculties enhanced.

I say, philosophy has all of this same power but in a superior magnitude, for the state of one’s perception, consumed by the philosophical world of any systematic philosopher, will produce an artifice more complete in its elements (the entire world of perception ) than any writing of Shakespeare and Dryden, or any painting of gustav moreau, or any song of Schubert’s.

Thanks, I enjoyed reading this. The experience of experiencing art can be hard to explain, but you’ve captured it quite nicely.