Before I plunge into deep and possibly murky waters, I should note that many do not believe in art. Not that they disbelieve in it. They are just not engaged by art or they view it as an amenity, a distraction, that requires no great investment of faith. But those of us who are engaged by art, who care about it, must of necessity believe in its value. Lacking that sort of belief, we would join the large, milling of the superficial and the indifferent. We who believe in art don’t talk much about our belief because we feel justified in taking it for granted. Of course, our interest in art is fostered by the feeling that it is in some way valuable. But in what way, exactly? This question is the upshot of fretting over something I mentioned in a recent post: Harold Rosenberg’s policy of assigning Mark Rothko to “the theological sector of Abstract Expressionism,” along with Gottlieb, Newman, Clyfford Still, and Ad Reinhardt. My fear is that, by quoting Rosenberg, I opened the way to a confusion between religious faith and faith in art—though confusion is not the right word if we agree with all those writers who have seen art and religion as aspects of one another.

This view emerged during the Romantic era and persisted even as art began to prevail over religion among those who felt that historical research and scientific progress undermined the authority of Scriptural dogma. Those historians who embarked on a search for the historical Jesus put questions to much of that dogma, especially the doctrine of virgin birth. Charles Darwin’s speculations about evolution joined with the study of fossils to undermine the story that the various animals appeared, fully formed, on the sixth day of creation. Nonetheless, modern doubt did not eradicate from every modern mind the religious belief—or feeling—that the universe is coherent and ultimately good. Art’s power to sustain the same feeling inspires the idea that art and religion are deeply connected and, in their depths, indistinguishable.

Writing in 1927, the philosopher George Santayana said, “Religion and poetry are identical in essence, and differ merely in the way they are attached to practical affairs. Poetry is called religion when it intervenes in life, and religion, when it merely supervenes upon life, is seen to be nothing but poetry.” Nearly half a century earlier, the Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold wrote that “more and more, mankind will discover that we have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us. Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry.” What Arnold and Santayana said about poetry can be extended to all works of art in whatever medium, and so we hear Rosenberg remarking on “the theological sector of Abstract Expressionism.” Among painters, poets, composers, and artists of every kind are those who seek what Rosenberg called “ultimate meaning”—meaning that is transcendent and indubitable and sought as well by religious sensibilities. The trouble is that the meanings of art are neither transcendent nor indubitable—not, at least, in my view of art.

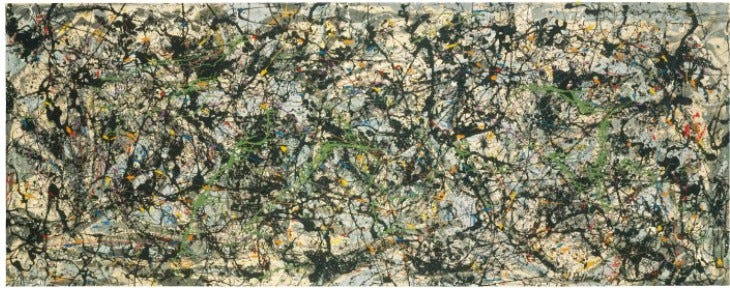

Plato believed, as I do, that works of art do not deliver the truth. Yet his reasons for his belief are nothing like my own. I am a poet with a pragmatist allergy to metaphysics, so I have no sympathy for Platonism, Neoplatonism, or any philosophical system designed to produce irrefutable arguments for or against art’s truthfulness. As I have said before, I see art as a source not of truth but of intuited and thus elusive meaning of the kind we do not discover in paintings and poems so much as invent when we swim in currents of aesthetic experience. This meaning is never ultimate, always revisable, and sometimes feels unsatisfactory. I have been writing about Jackson Pollock’s dripped and spattered canvases for decades. Will I ever say with any certitude what his imagery means? No, I won’t because I can’t.

Works qualify as works of art only if they resist the protocols of certitude. A competent illustration makes its meaning clear and may even convey the truth about something. An honest documentary image does the same. But the point of an artwork is to remain forever open to interpretation. The instances of openness we find in paintings, poems, and musical compositions are valuable because they offer condensed, exemplary variations on the irresolvable nature of the world’s conundrums. I do not, of course, deny that we know many truths about the world and the lives we lead in it. But we cannot know for sure what these truths mean. You say, convincingly, that you truly love a certain person. I am convinced, but when I ask you what it means that you love this person you will either resort to empty clichés or begin, very quickly, to stumble over your words. Meaning is elusive.

There are solid, art-historical reasons to believe, for example, that the Pollock catalogue raisonné is telling the truth when it says he painted Lucifer in 1947. There are, however, no solid reasons for believing that the painting merges the artist’s idea of himself with his vision of the infinite. Yet this is what I believe. The difference between belief of this sort and religious belief is stark. To say you believe in God is to say, among other things, that you believe God exists. That you believe in the truth of God’s existence. But if I say that I believe in Pollock’s power to evoke the infinite I am not saying that, in truth, he does evoke the infinite. For the issue here is meaning, not truth, and speculations about meaning are neither true nor false. So, whenever I give an account of an artwork’s meaning I neither believe nor disbelieve that my account is true. I believe in my account because—for me and for now—it is valuable, significant, and full of potential for further meaning. As I see it, to believe in art is to take a leap not into a void but into a plenitude of possibilities where nothing keeps you from crashing, nothing saves your life, but your ability to make sense, however provisional, of art’s endless and spectacular ambiguities.

These days I have been thinking about what words cannot impart. I live in a mixed-language household and the issue of nuance and cultural interpretation arise, probably more frequently than I’m even aware. To put a Rothko into the country of the OED takes away its passport, for me.

This current demand to describe, to interpret, to demystify artwork for easy consumption, predigestion (for the internet) can feel tyrannical to the non-verbose. There is a world beyond “storytelling.”

The striving for meaning, interpretation, exists in the land of nouns and verbs. I’m thinking of the frisson where color cannot meet language.

Yes, language is necessary, but what of Pollack reminding me of childhood? He makes me think of playing hide and seek amongst brambles, where the brain is in pattern recognition mode, taking us back to the uhr-hunt where the visual and aural reign. That is the power of abstraction, particularly the unphotographable. The Pollack and the Rothko are experiential.

I leave the words to others, except this morning, as I sit by the water and have my coffee, as the perpetuity of waves move far beyond human history, of language.

Thank you for making your beliefs so clear. Certainly, Art and Religion are distinct disciplines and operations too. Religious Art is very different from 'spiritual ' art or 'theological works'. It really is a simple thing: Religious art depicts its principles and beliefs; it advocates directly; we are instructed how to believe without words ( think of the Raphael Mother and Child works or Buddhist works ). Dicates is not the right word, but directives to a principle like "sacred family" or " nirvana", is the clear operation of such works. On the other hand, art works induce feelings and meanings suggestive of other states of mind, "infinite", "elusive","sublime", "memorial"--- as each viewer may perceive and share.

The Late Baroque Aestheticians and Philosophers went to much trouble confounding these matters, evidently to entitle fine art that was Not religious with values that need not have been transcribed--- the non religious works had their own values and meanings anyway. !

This is a fine essay and contribution to a complex subject . Your thinking is clear and helpful. Thanks !