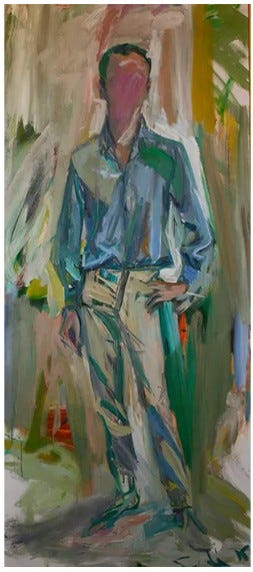

Elaine de Kooning’s early paintings are too much like her husband Willem’s, a similarity she came to see as a hindrance. By the mid-1950s, she had disentangled her style from his, exchanging Willemesque shapes for flurries of brushstrokes at once feathery and vigorous. The springy energy of her mature paintings sometimes seems forced; more often, she charts her subjects’ forms with elegance and verve. Elaine de Kooning stands out among the second-generation Abstract Expressionists. And she was a brilliant writer, better in a crucial way than Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg. Her superiority is a matter of scale.

Neither Greenberg nor Rosenberg could stop themselves from making big, absolutist statements on form (Greenberg) or content (Rosenberg). Their grandiosity led them into swamps of pontification where criticism loses touch with art’s immediacies. Elaine de Kooning’s commentary always bears directly on experience—the viewer’s as well as the artist’s. In an essay entitled “Subject: What, how or who?” (published in the May 1955 issue of ArtNews and included in a selection of her writings entitled The Spirit of Abstract Expressionism), she wrote:

The artist cannot pick or avoid a subject except through a style, and that style automatically becomes part of his subject. You can be influenced by the style of Géricault and paint an abstraction. You can be influenced by the style of Kandinsky and paint a landscape. Influence always rides on style, never on subject. But styles always begin with ideas about a subject. A style in art, when it is vital, is a mode of thinking.

To deploy a style is to think. This is a surprising claim. In his Observations on Painting, a compendium of bits and pieces borrowed from earlier writers, the seventeenth-century classicist Nicolas Poussin said, “Style is a particular manner and skill in painting and drawing which comes from the particular genius of each individual in his way of applying and using ideas.” Style expresses the self from which it originates. A commonplace in Poussin’s time, we still find this notion serviceable. During the eighteenth century, the stricter French classicists (Dominique Bouhours, Yves-Marie André) understood style as impersonal: a set of decorous pictorial devices that comport, when successful, with the larger decorum of a well-wrought composition. Style-as-self-expression survived this swerve into rigor, modified only by nationalist enthusiasms that inspired the idea of style as the expression not of an individual but of a culture. That idea lingers and yet style as the self’s imprint dominates. Think of the phrase “signature style.”

In a 1991 interview, the German painter Martin Kippenberger said,

In no way do I have a style. The evidence for this is already there in my childhood. My father always told me I really had to have a style, and I was terrified that I would never be able to bring off a Chagall or a Dubuffet, the kind of stuff we had at home. Until I realized that my style is just where the personality is.

To have a self is to have a style. Not every artist has been happy with that. “Style is a fraud,” said Willem de Kooning in 1949. He said it but he didn’t mean it, or not exactly. After all, he never denied the obvious: his career, like Picasso’s, owed its shape to a succession of styles. De Kooning directed his charge of fraud against the carefully thought-out geometries of Piet Mondrian and the other de Stijl painters, who devised their severe manner in the hope of rendering all other styles obsolete. That sort of calculation is driven by “a bourgeois idea,” said de Kooning. I’m not sure what makes it “bourgeois.” Maybe he thought that de Stijl’s determination to win the race to the avant-garde future aligned the group with those marketeers who offer their products as the newest and the freshest and therefore must-haves for the alert consumer.

Willem de Kooning’s remarks about style are dismissive, possibly because he feared that too much talk about the subject would produce stilted brushwork. Feeling no such fears, Elaine de Kooning wrote about style in detail and did that rare thing: she came up with an original idea. No one else, from Poussin’s time to ours, has said that style is “a mode of thinking.” But what does she mean by thinking? She does not mean the rationality that seeks coherence in data or ideas we already have. The thinking she has in mind is creative and not easily distinguished from the imagination celebrated by the Romantic poets, S. T. Coleridge especially. But Coleridge placed style on a continuum from humble to elevated (qualities of character) and never came close to connecting it with creative thinking.

For Elaine de Kooning, the artist’s thinking is the faculty that produces new images and of course new styles. So style-as-thinking comes into play as an active, generative force, energized by the artist’s attitudes, yearnings, and beliefs about the way the world should be. Style in her sense of the word creates the subject and in the process merges with it. For her, style and subject are one.

De Kooning’s idea that style is a mode of creative thinking helps us see that a painter’s command of her powers is greater than we usually acknowledge. And she exercises this power with every touch of brush or pencil. To paint is not merely to choose a motif and get it down on canvas in a style that counts only as evidence of the artist’s personality. When she paints, the artist guides her visual thought through a range of possibilities: speculating, revising, and speculating further until a resolution emerges. The finished painting will bear traces of her character, inevitably, but, more than that, it will show us her way of being in the world.

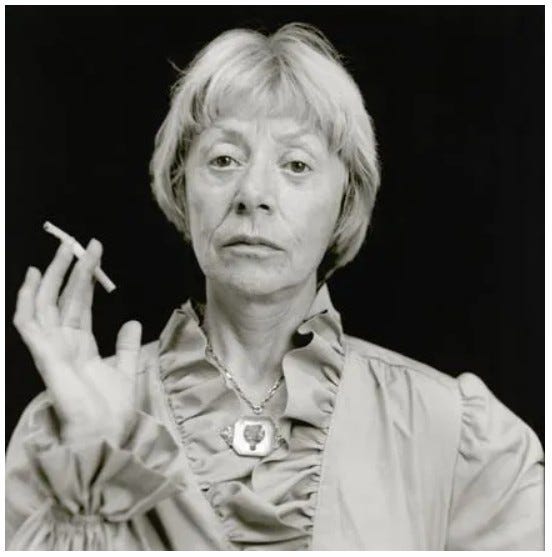

I met her a few times in the early 70's. She came to my first show at fischbach gallery in 71 and I liked her. Remember her red hair and her smile. I also went to a party at her loft I recall on lower broadway or university ave. The thing I recall about the loft was the floor slanted. Wish I had gotten to know her better.

I’ll have to read this several times bc I have struggled with “what is my style” for forty-five years. Series have a style of painting. Maybe the ones that happen between series are forecasting. I would have to say that, literally, style is how i use and manipulate paint. Thank you fir writing about Elaine.