In the September 2013 issue of The Brooklyn Rail, I published an essay entitled “What Is Art?—and Why Even Ask? Here it is, with a few revisions.

Long ago, Willem de Kooning and John Cage were sitting in one of the downtown cafeterias that New York artists used to frequent. Throwing a couple of packets of sugar on the table, Cage said, “This could be art.” De Kooning’s reply: “No it couldn’t.” Neither Cage, practitioner of the I Ching, nor de Kooning, an academically trained painter, was persuaded, then or later, by the other’s remarks. Yet I am nagged by the memory of this exchange, for it implies a question: what is art? On the heels of this question comes another: do we need to corral art in a definition? For the past decade or so, my answer to the latter question was yes, and I offered a definition of my own.

In a series of lectures and essays I said that a work of art must be endlessly interpretable. To this claim one might say, “Lots of things are endlessly interpretable. What about a psyche? What about a society?” Well, neither one of those is a work (despite Jakob Burckhardt’s notion of the Renaissance city-state as a work of art). Nor are they intended to be endlessly open to interpretation—for that was another criterion of my definition: to count as a work of art, the work in question had to be meant to be open in that manner. Further, it had to be meant by an individual. Intention would always be in part unconscious and the individual might be a duo, like Gilbert and George, or even a collective, but the maker of the work had to be, in some sense, singular. The main point was that there could be in principle no end to finding meaning in the work. Artworks are inexhaustible.

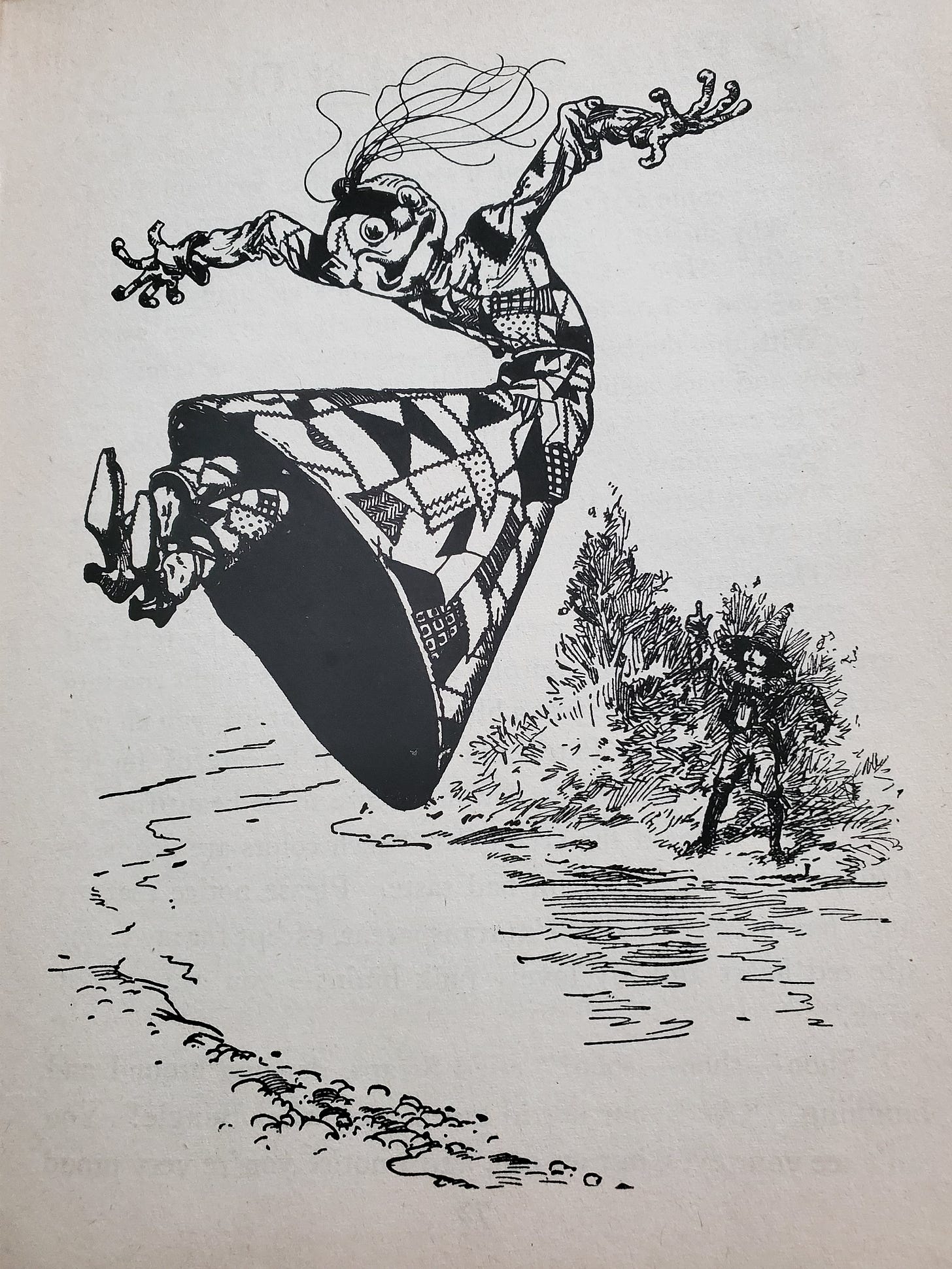

By contrast, an illustration is exhaustible. You see what is being illustrated and interpretation comes to an end. Of course the Patchwork Girl of Oz raises many social, cultural, and political questions about which grownups have had much to say. But John R. Neill did not mean his picture of this character to be, in itself, endlessly interpretable. You quickly get his illustrative point and that is the end of it.

Likewise, you get the point of a documentary work and that is the end of it. You get the point of a decorative image and that is the end of it. Illustration, documentation, and decoration are exhaustible. Art is not.

I came up with this definition of art because I saw the exhaustible taking up space that should have been occupied by the inexhaustible. Art, as I saw it, was being crowded out and this seemed a shame because I believed and still believe that the interpretation of an artwork becomes, if you stick with it long and passionately enough, self-interpretation. The discovery of meaning in art becomes self-discovery, even self-transformation. But this can happen only if meaning is inexhaustible. I love illustration (not only Neill’s Oz images but Arthur Rackham’s pictures for The Wind in the Willows). I fully appreciate the work of powerful documentarians. And we all like whatever decorative scheme suits our taste. Nonetheless, illustration, documentation, and decoration cannot offer what art offers, and I felt it was important to define art in a way that brings into focus its peculiar generosity.

Then, not so long ago, I told the poet George Quasha my definition of art and he was reminded of a course he had taken with an aesthetician named Morris Weitz, who argued that no definition of art is logically defensible. In an essay called “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics,” Weitz argues that such definitions are always partial, not to say, biased. Rather than establishing the necessary and sufficient traits that would qualify a work as a work of art, they state preferences. Convinced, I realized that, in excluding illustration, documentation, and decoration from the realm of art, I was stacking the deck in favor of the art I preferred—the painting, for example, that Ishmael finds at the Spouter-Inn, in the third chapter of Moby-Dick. This canvas is filled with such “unaccountable masses of shades and shadows” that he sees it at first as an image of “chaos bewitched.” Eventually, he makes out a picture of a whale and a foundering ship—case closed, you might say. Interpretation has reached its conclusion. Then, as you read on, you realize that the implications of this image of boat and whale pervade the immensity of Melville’s novel, shifting as his themes and rhetorical devices shift. So, all right, this is the inexhaustibly mutable sort of art that I prefer. But I recognize my preference for what it is and no longer advance a definition that would exclude illustration and other kinds of work from art’s realm. What, then, was the point of asking for a definition of art?

Think back to Cage and de Kooning at their cafeteria table. With no hope of agreement, they took delight in proclaiming their differences. Why? As I said, artists’ intentions are at least partially unconscious. With the exception of those happy to settle into a rut, artists try to bring their intentions to light—to clarify and strengthen and even reinvent them. Coming up against another’s incompatible intentions can speed the process. Awareness of who you are not can help you see who you are—or might become. In an essay called “Essentially Contested Concepts,” the philosopher W. B. Gallie presented art as a prime example (others were democracy and justice). His idea that certain concepts are not only contestable but, by their nature, endlessly contested is useful because it points to the possibility that our myriad ideas of art owe some of their vigor to the challenges they face. We ask “What is art?” not to settle the question but to force ourselves up against the impossibility of settling it—an impossibility worth noting as explicitly as we can, for it is what keeps art open and present and therefore alive.

Yes, but what’s the difference between art and valuable art. Or, is the question relevant because it was between De Kooning and Cage

I would like to extend a comment: "Illustration, documentation, and decoration are exhaustible. Art is not."

The interpretations of art are endless. Indeed, every generation sees more meanings upon those previous ones. There are other types of visual works that exhaust their interpretations quickly. Indeed, they are made to do so immediately. Social statements, sloganeering, political and social art professes to communicate their platforms. Those visual works have a purpose : get this viewer ! and do something since you see the sign !! They intend to exhaust their interpretations in one go : get this.!

// This explains why there are few interpretations(other than the de-constructions of their de-construction); none are intended or desired. And this is why those works are so limited and live only for the one exhibition or demonstration. /// Those types of works may be useful for their immediate communique, but that is the end of it for them. The life of those works is, by their own purpose, short.