This is an excerpt from an essay I published in 1994, in response to “Willem de Kooning: Paintings,” at the National Gallery, in Washington, D. C.

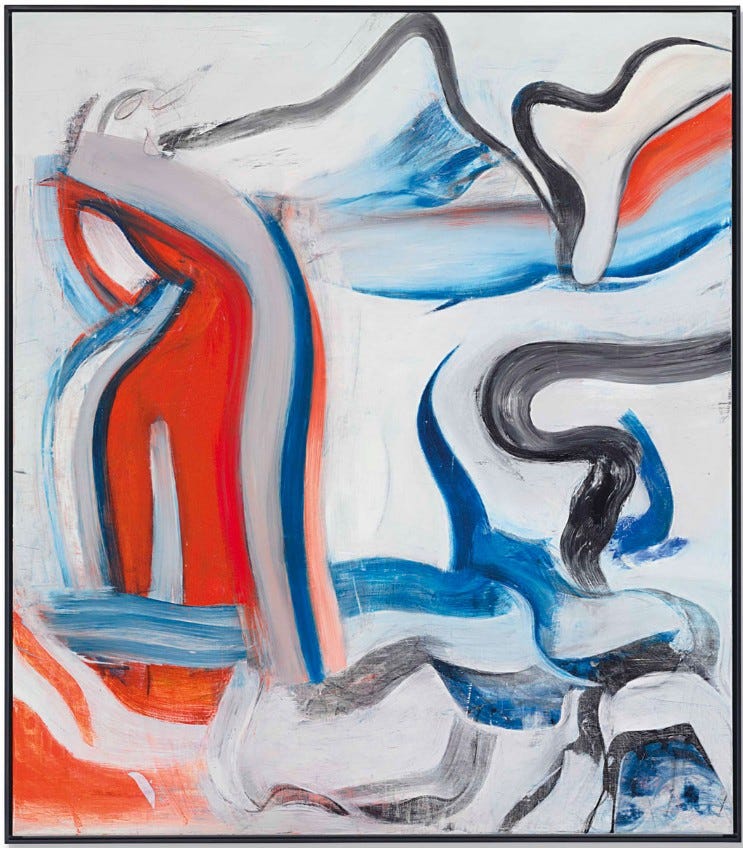

At every big de Kooning show I find that a new batch of his pictures has become my favorite. At the Museum of Modern Art in 1968, my best-in-show vote went to the works that Thomas Hess, the curator of that exhibition, called “abstract urban landscapes”—pictures like Gotham News, 1955–56, and Police Gazette, 1954–55. (Both reappeared at the National Gallery, though Gotham News will return to the Albright-Knox, in Buffalo, without stopping off at the Met.) This time I liked best of all the “abstract parkway landscapes” of 1957–60, and especially Montauk Highway, 1958, and Door to the River, 1960. I even came away from the show with a favorite color: not the deep, luminous blue stretching across the upper reaches of these pictures but the bruised-looking ocher that manages to remind me not only of raw, bulldozed earth but also a quality of North Atlantic light in autumn—afternoon light filtered through leaves that have turned. These de Koonings have virtues in common with the best picture postcards.

“Abstract parkway landscapes” is Hess’ phrase, invented for the catalogue of the 1968 MoMA exhibition. He was responding to de Kooning’s offhand eulogies of “weekend drives.” “I like New York City,” de Kooning said in 1960, “but I love to go out in a car… I’m just crazy about going over the roads and highways … the big embankments and the shoulders of the roads, and the curves are flawless—the lawning of it, the grass. This I don’t particularly like or dislike, but I wholly approve of it.” “It” is several things: the highway system that connects city and country and has the scale of both, and that system’s “flawless,” boring design and execution. De Kooning’s parkway landscapes have the scale of this big-time American engineering, and some of its shapes: wide straightaways and curves with a slow, arrogant sweep. Those who know the East Coast can hardly avoid reading Long Island’s flatness into Montauk Highway. Door to the River seems to set the highway or the rush of it alongside architecture at the edge of Manhattan, which is to say the river’s edge, though you could just as easily say that de Kooning is referring here to some large, light-shot place out of town.

These pictures offer no simple dichotomy of city versus country. They are about a third term, the connection between the first two, a linkage rendered in ways that throw all terms in doubt. In the late ’50s, de Kooning’s idea of the countryside was fairly sketchy, a variant on his idea of the city, which was intricate and far from tidy. Though de Kooning grew up in Rotterdam, he spent most of his adult life in New York, a messy place all out of European scale. New York is inhabited by an idea of America as the realm of infinite possibility and the pressure of that idea pushes all the large gestures in the parkway landscapes.

Yet de Kooning never accepted America’s most expansive notions about itself. He is in general a skeptic, a man who once said, at the Club, “We are all basing our work on paintings in whose ideas we no longer believe.” And to carry out the shift of style that produced the parkway landscapes, he worked from an idea of himself that did not quite cohere. Leaving himself a bit behind, he made a few steps in the direction of Franz Kline. The wide swaths of color in the “abstract parkway landscapes” give them the look of Klines in color, though they appeared before Kline himself had switched from black and white to a fuller palette. By 1956, a number of New York painters had looked at the structures Kline built from beams and struts of black paint and decided he had the right way to get pigment onto canvas. You see the force of his example in pictures by Elaine de Kooning, Al Held, Michael Goldberg, Alfred Leslie, Joan Mitchell, and others—artists often considered followers of de Kooning. In the parkway landscapes, Willem himself found uses for Kline’s boldness. Even so, his mix of delicacy and brusque urgency is always recognizably his.

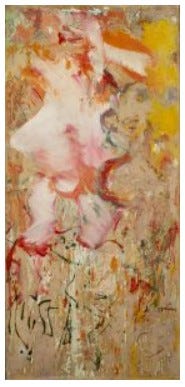

Parkways led de Kooning from Manhattan to Springs, on Long Island, where he settled in 1963. Urban angularity disappeared from his pictures as he let himself be entranced by the shimmer of light on water and the country’s lush curves, and de Kooning entered the last and most unapologetic of his calendar-girl periods. Before, by dread or an idea of refinement had tempered his leer. Wallowing now in pink, he mixed Rubens and Soutine.

Skipping around the sculptures that preoccupied de Kooning in 1973–74, the Washington show has a small but strong selection of the paintings he made between 1975 and ’78. In these grand, skidding pictures he revives his Manhattan arias in a mood at once elegiac and panicky. Because they are as crowded and grandly jerry-built as Police Gazette or Gotham News, these works do not feel like summaries. Only in the late 1970s did the summation begin, leading de Kooning back to clarities as sparse as the ones you see in his abstractions of the ’30s, when he was still a provincial Modernist looking for the master logic of his medium. What de Kooning clarifies in these late works is the habitual shape, the characteristic thrust and torque, of the gestures he began to make when he realized that there is no master logic and that he would have to rely on his personality.

Is de Kooning America’s best European painter? Europe’s best American painter? He is deliberately, provokingly elusive, and he gives that quality to his subjects. “The landscape is in the Woman,” he said, “and there is Woman in the landscapes.” By the mid ’50s, her massively voluptuous shapes had merged with drifts of cloud and water and terrain. De Kooning said he “could sustain this thing all the time because it could change all the time; she . . . could not be there, or come back again, she could be any size.” She could be either sex. “You can’t always tell a man from a woman in my painting,” he noted, adding, “Those women are perhaps the feminine side of me—but with big shoulders. I’m not so big, but I’m very masculine and this masculinity mixed up with femininity comes out on the canvas.” Maybe we could take away a lesson here about the provisional nature of the self.

If so, de Kooning was not what Harold Rosenberg wanted him to be: the action painter who examines his painting in progress for “the true image of his identity.” The Rosenbergian painter “accepts as real only that which he is in the process of creating”—himself and the self-image that are in essence identical. For de Kooning, much more than that was real, or real enough: the past, the ordinary world, low art, the art world and its politics of style. Rosenberg’s action painter is an earnest, existentializing chap alive to nothing but a melodrama about his own authenticity. De Kooning’s paintings teach a better—anyway, a more amusing—way to be: alert and responsive to the tireless variety of high culture and the world beyond its porous borders.

De Kooning is always driven by something small, a fragment of the world or drift of feeling—the “flash,” the “glimpse,” that he talked about on occasion, a private experience that he renders public at a large scale. It is an art that encourages us to invent stories, maybe, but not to extract any moral. Uneasy in the absence of didactic rewards, we may let the pleasure of de Kooning’s art elude us. And even if we don’t, we may still ask: what is the point? This question is unanswerable, yet it lingers, so let me make this suggestion. In the pleasures of paintings as complex as de Kooning’s, we can glimpse an allegory of utopian happiness. For if society were to fit our sensibilities as well as the universe of his imagery fits his, we would indeed be citizens of a perfected realm. Everything would work, both perfectly and with surprises, so our utopia would not be boring. All major art offers this utopian allegory, which is also a reproach: life may never work as well as art, but can’t we learn anything from art’s example? To avoid the reproach, we overlook the allegory and miss the one moral argument that the skeptical de Kooning was willing to make.

The characterization of these fantastic works as "Urban Utopias' (maybe Urban-Suburban Utopias) is so accurate. They are a epitones of that time as well. They do proffer a happiness. Indeed, they come from and fit that period of American ebullience with its promise of a perfect happiness. The paintings are just gorgeous, with the grey sympathies and beams of bright tonalites in balance.

The allegory in his works can be compared to other works in that period:

To jump media, look at the films of Antonioni ,L'Avventura (1960), putting black & white juxtapositions between eternal essential values and flirtatious existential values. Frustrated and capricious young lovers are tormented by their impulses, while bonded older couples holding hands stroll along in the backgrounds, interrupted occasionally by orders of nuns marching through the scenes of disloyalties. One of the young women disappear on the adventure, and no one is quite sure whether she existed at all, and finally, care even less.

Antonioni broadened his essence/existence value portrait in the Passenger 1975. Can we recall the Actor Jack Nicholson sweating out the dysfunctional jeep in the blazing desert, cursing his fate rather than acknowledging his essential meaning. ?? The Passenger ends where he started, wiped out by his own misdeeds and inability to recognize his inherit merit.

To cross back to paintings in that 1955-1970 period , the Rothkos and Newmans mesmerize us with the suggestion of another dimension. They whisper of another realm of values, alluring the eye and spirit into another type of Allegory. The meanings in Vir Heroicus Sublimis are complex and inspirational; that Allegory appeals without condition. We are given a vision of a sublime certainty, solid as the square essense at its center.

The Rothkos entice and suggest a penumbral world that we can barely grasp, like those shadows on the cave walls that Plato sites as reflections of ultimate things, eternal values.

I write these cross references to show that other works of that period presented Allegories of full promise, displaying meanings that can bring participants into more wonderful lives. Such works differ from the existential struggles of identity in Kline and De Kooning, because the identity of their makers was felt sound BEFORE they started painting, rather than revealed or bungeled in the painting struggle, as Jack with his jammed-up jeep.

My studio is working to make pieces that reveal the essential glories of consciousness, the new wonders and beauty that we can perceive and know by digital means in our Virtual Era.